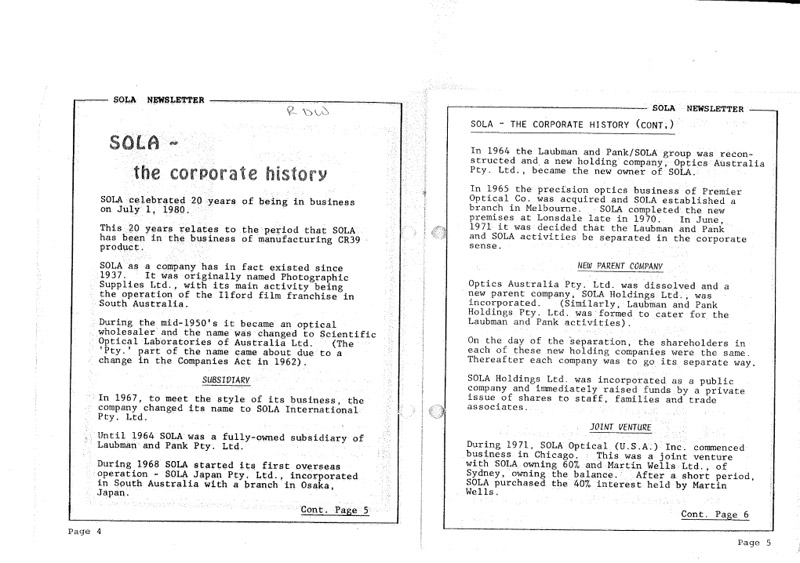

4.3 Global Manufacturing

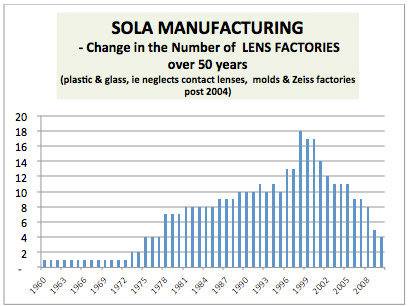

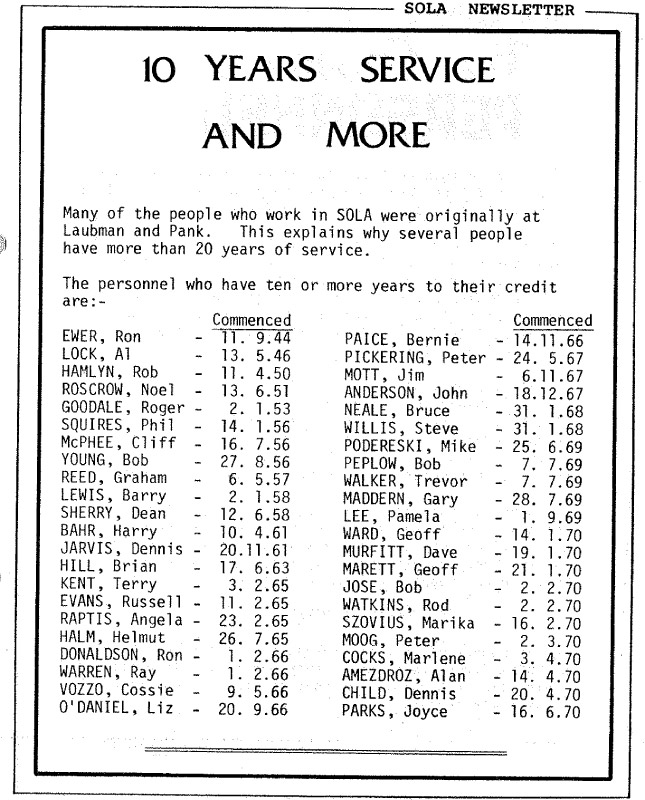

SOLA started with one factory in 1960 and, by a combination of Greenfield sites and acquisitions, peaked at 18 factories with a global distribution (North, Central and South America, mainland Europe and Ireland, Asia and Australia). Today there are the big three ex SOLA factories in Mexico, China and Brazil. As well there is a relatively small polycarbonate sunlens factory in China.

The decrease in the number of factories does not directly relate to the decrease in SOLA's skills, competency or in the number of lenses produced as some factories were closed and the volume migrated to other factories.

Jeremy Bishop:

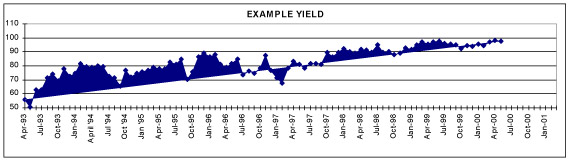

In fact it's a graph that many would be fairly proud of. There are many reasons to justify a belief that a significant part of SOLA's financial woes stemmed from the large number of factories and the complete lack of coordinated manufacturing that existed up to the mid-late 1990's.

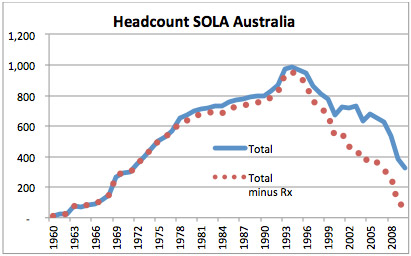

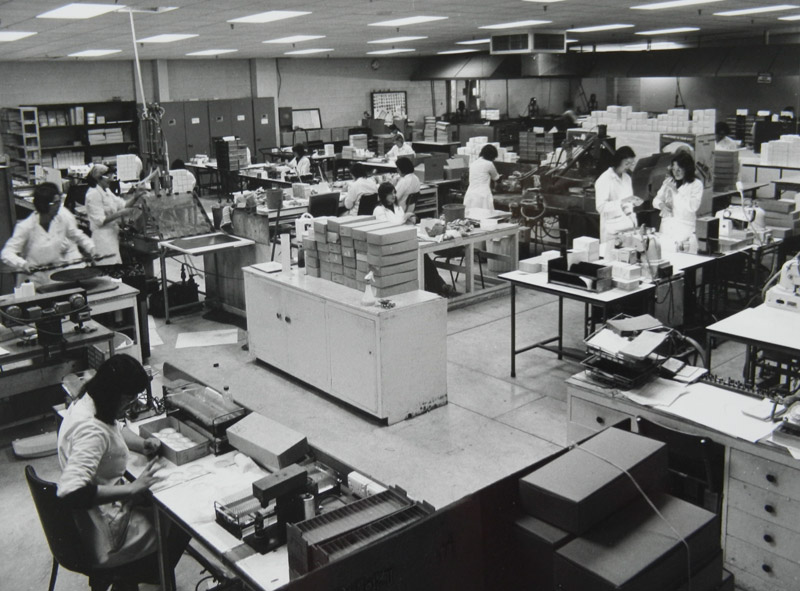

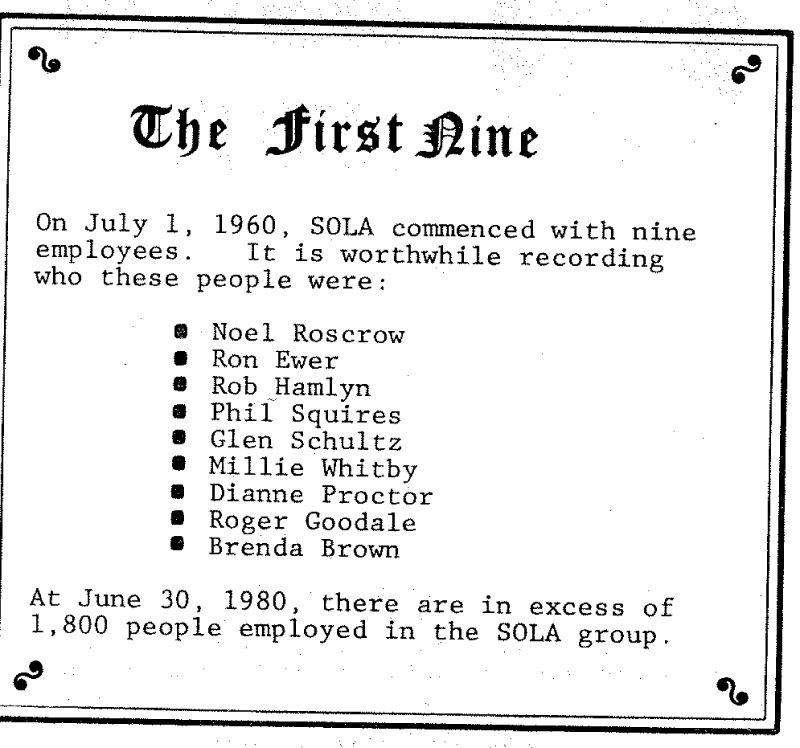

The change in the Australian operation over the 50 years is particularly striking:-

SOLA Australia started with 9 employees, peaked at just under 1,000, and by March 2010 had 328 of which 245 worked in Rx and the 83 others covered a mixture of Corporate and R&D roles.

Australia’s fate was similar to North America and Europe where all SOLA lens manufacturing sites have also been closed.

Regional vs. Front Office/Back Office Management Structure

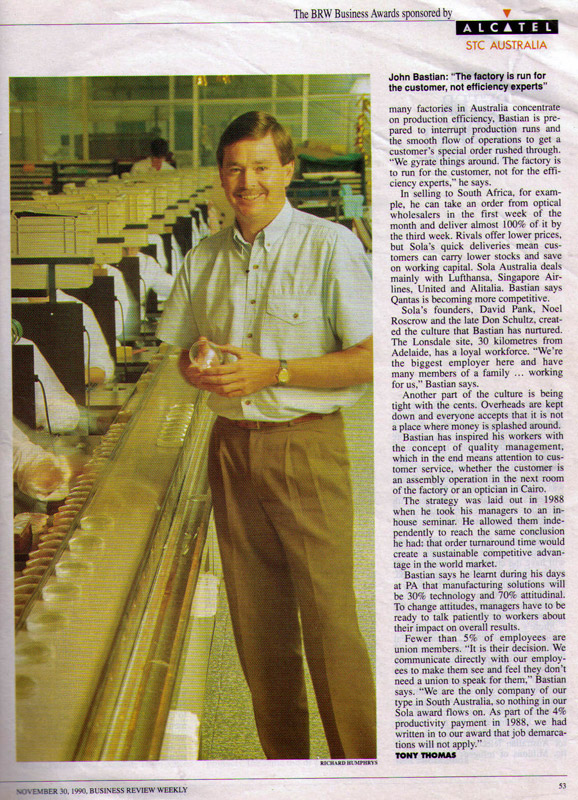

Several times during the last 40 years SOLA/CZV alternated from a global structure based on regions to one based on Front Office (sales/marketing) and Back Office (manufacturing/supply chain). Each had its advantages and disadvantages. In the early days the Regional structure sometimes caused much friction between Regions, sometimes to such an extent that another region of SOLA was viewed as the enemy.

The Regional structure did allow greater synergies between sales and manufacturing within a region, but not always to the good of the group. In the 1990s and 2000s the alternate structure resulted in generally amazingly constructive cooperation between the manufacturing sites. Barry Packham presided over a fantastic group of manufacturing and supply chain managers (with a wide cultural diversity) that worked well together for the overall good of the company, followed similarly by Jon Westover with global manufacturing. The 6 monthly face-to-face meetings generally over 3 days at a manufacturing site, also helped the bonding process and was a key to ensuring the ongoing cooperation of all manufacturing sites.

Global Operations April 2000 – April 2003 Barry Packham

Pre-1999 SOLA had a regionalized structure with minimal centralized support functions.

Late 1999, John Heine creates the back office/front office structure. Front office is broken into commercial regions including Rx labs and distribution.

Bret Olsen is given North and South America commercial. Barry Weitzenberg losses NA commercial, retains factories including OSM.

Jim Cox is given back office (global manufacturing). Brazil and Venezuela report to Cox directly, but in practice through Jorge Mario.

Tony Donegan gets Europe Commercial and Alan Vaughan European manufacturing reporting to Cox.

Group Manufacturing Development reports to Cox.

In April 2000 Jeremy Bishop becomes SOLA CEO, appointing Barry Packham leader of back office, adding distribution (supply chain) to back office. Jim Cox becomes leader of R&D and Business Development. Cox resigns a couple of months later to become CEO of the small and struggling Rodenstock USA.

Tony Donegan resigns to become GM of an Irish engineering firm - Kent Engineering, based in Wexford, which does quite a bit of work with SOLA. Mark Ashcroft becomes the new leader of European Commercial.

The beginning of Global Operations saw some immediate threat-to-survival issues dominated by two main factors:

- Manufacturing & supply chain improvement (the pressing need to dramatically reduce unit cost & working capital, and improve customer service level and quality).

- A rapidly declining route to market due to Rx lab acquisitions by competitor lens manufacturers, notably Essilor, and especially so in the USA.

These two factors threatened the existence of SOLA. Other factors, such as improving the new products stream were also of pressing importance.

The Global Operations Strategic Plan of Dec 2001 had the top priorities as:

Manufacturing

- Compliance

- Polycarbonate expansion

- Completion of Global specifications

- Completion of OSM, Mexico restructuring

- Transitions Sapphire

- Building SGJ, China capacity and competence (hard and AR coating)

- Building SBIO Brazil hard coating capacity and competence

- Migration (including the exit of SOT, Taiwan and NOSL, China)

- Global quality consistency and improvement

- Direct cost down and overhead containment

Logistics

- Completion of Logistics restructuring

- Reduction in inventory levels through balanced inventory, compliance and reduced lead times while maintaining or improving customer service

- SCIP

- FRS

- UPS

- Implementation of a formal Global Supply Chain process

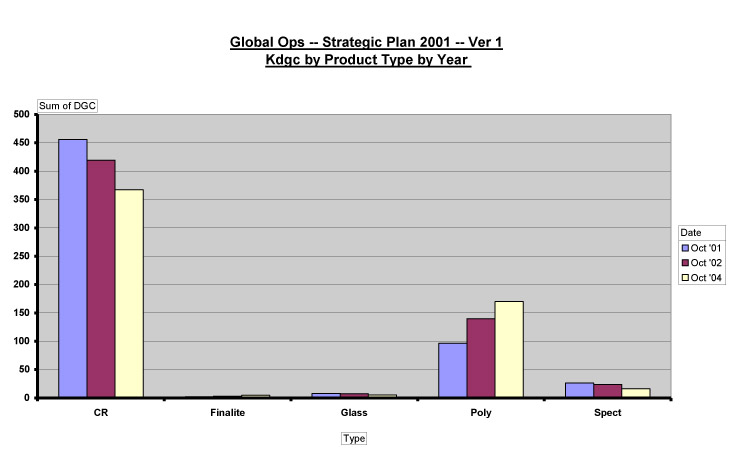

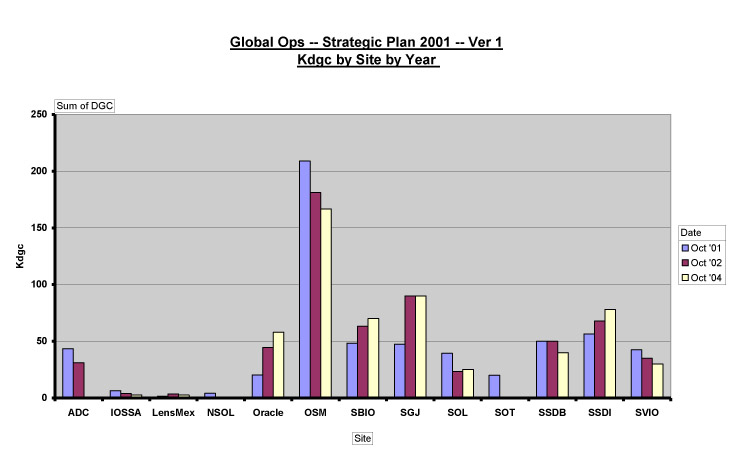

The forecast lens volumes, by material and by site, in the Strategic Plan of Dec 2001 were:

In 2001, Global Operations had a headcount of 5,236 made up of:

- North America, including AO manufacturing 2,087 (1,700 in Mexico)

- Asia-Pacific 1,050

- Europe/Venezuela manufacturing 685

- Brazil manufacturing, ophthalmic 623 and planos 198

- Distribution (mainly) 687

Average total daily lens production was 777,327 made up of 519,019 ophthalmic and 258,308 planos.

Americas

The absorption of the AO LensMex factory production into OSM Tijuana in 1999 had created a huge indigestion problem for OSM. In early 2000 there were 500,000 to 600,000 lenses on backorder at any given day, a great deal for a factory that was at the time casting 160,000 to 180,000 lenses per day. The effect in the market on SOLA’s customers and reputation was dramatic, with our main chain retailers, Wal*Mart and Lenscrafters amongst others threatening withdrawal of their business.

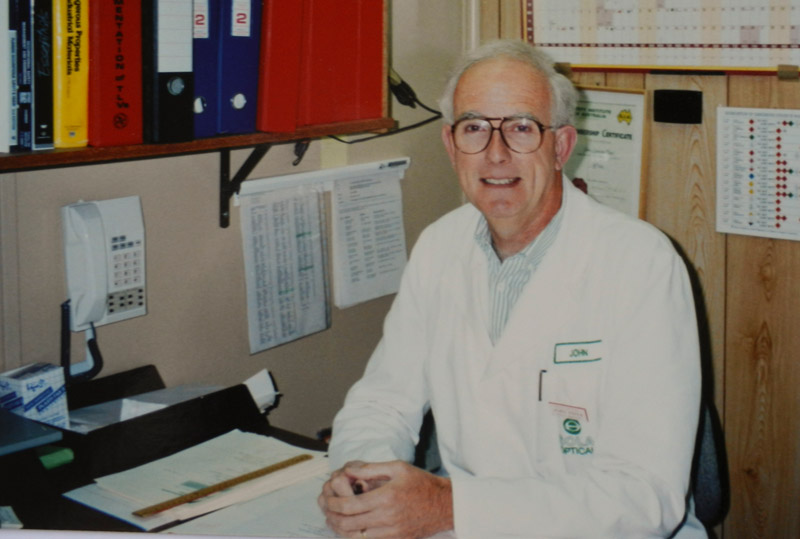

Barry Packham sets up an office at OSM and together with plant manager Alejandro Flores began concentrating SOLA’s best operational and technical resources on rectifying the situation. Amongst others to answer the call for help were Kym Gibbons, Bob Sothman and Mike Pittolo.

- Demand replenishment systems driven from Petaluma were reviewed in fine detail by Kym and Debbie Wheeler, resulting in several crucial refinements being made within weeks, resulting in far more precise lens-by-lens ordering on the factory.

- Shop floor compliance systems were developed on the run to ensure that only the required molds were being held in the casting lines, and every lens cast was electronically logged against the demand plan. Soon only the “right” lenses were being made.

- Simultaneously Mike Pittolo and Roy Miramontes oversaw considerable tightening of production processes and quality systems.

By late 2000 backorders were being measured in the 100s, averting the threatened customer withdrawal, and after Jon Westover took up leadership of OSM following Alejandro Flores’ retirement in July 2001, backorders were driven further down – the best recorded day being two lenses on backorder – the ambitious zero lens backorder day eluded us, but it spoke volumes for the honesty of everyone involved that no effort was ever made to “fake” a zero backorder day.

At the same time Packham determined to close the Petaluma manufacturing facility at Cader Lane, move all manufacturing to Mexico and sell the land and building. The property eventually sold for some $11 million in a falling market. The money was very helpful during our 2000 /2001 cash crisis. Jon Westover moved to San Diego with Jackie and their growing family in early 2001 to oversee the migration of manufacturing and the closure of the site. On completion of this task with Jon’s usual no-nonsense efficiency and effectiveness, his next task was to take up leadership of OSM. This included the major undertaking of the expansion of the OSMII site and the closure of the old OSMI site, which Jon once again performed masterfully.

On the supply chain side, the North American network of 11 distribution centres was collapsed to two centres, one on the East coast in Kentucky, one on the West coast at San Diego. This was led by Joyce Maruniak and John Sedlander, who achieved the rationalization with only minor interruption to customer service. This yielded considerable working capital and labour savings, and contributed significantly to improving customer service. In late 2001 Paraic Begley took on the supply chain leadership role for North America, bringing customer service levels during 2002 to an all-time high for SOLA, and industry leader in North America as measured by the two largest retailers in the North American ophthalmic market, Luxottica and Wal*Mart.

Europe

Concurrently chronic customer service issues were affecting the European market. Initially Tom Higgins was appointed to bring a sea change in this metric. Tom’s first major task was to refashion the existing antiquated AO distribution centre in London into a modern high-rise centre, aimed to handle most of the European distribution requirements. Tom was followed by Mike McKeough in 2001. Mike succeeded in bringing customer service levels to those of our main competitor Essilor for the first time ever through a very hands-on approach.

Unit cost reduction was addressed principally through the “where-to-make” strategy, following on the heels of the very successful Rooster “how-to-make” program. This involved the progressive closure or reduction in size of many of the 18 SOLA factories scattered about the world, with the longer term goal of reducing the number of factories to just four high volume sites. The person who co-ordinated this massive migration program was Barry Sheridan – to become known as “The Web Master”.

The financial management of this complex web of closures and consolidations fell to David Cross, who moved with wife Randi from his role in Australia as CFO Pacific Region to San Diego to join Global Operations as VP Finance. David performed the task magnificently, with his as always infectious good humour and style.

Restructuring -The Way Forward? Steve Heilborn

There were a number of plant closures and consolidations from 1994 until 2009.

Colonial Heights, VA (previously Coburn Optical) was closed in 1994. David Provow, plant manager, led the transfer of CR-39 lens manufacturing to Tijuana, MX and the mold manufacture to Eldon, MO.

To facilitate the restructures, mold and mineral lens manufacturing was restructured from regionally managed organizations to a global organization under Steve Heilborn in 2000.

Steve became known for closing and migrating manufacturing sites. It was under Steve’s watch that multiple plants were closed and manufacturing relocated to other sites. Although it must be noted that several others also earned similar reputations during this time!

Eldon, MO, previously a Coburn Optical plant purchased by SOLA, was closed in 2001. The Plant Manager at the time, David Howard, assisted with the migration of mineral lens production to IOSSA, France and the mold manufacturing to Tijuana, MX.

Metal mold manufacturing in Petaluma, CA was closed and relocated in Tijuana, MX in 2003. This was the last manufacturing process in Petaluma, CA where 1,200 people had previously been employed.

Singapore mold manufacturing under the management of Peter Woo was closed in 2004 and the majority of molds migrated to Tijuana, MX. Some technically complex molds were migrated back to Adelaide, AU. The Singapore plant had been in operation for 30 years.

Southbridge, MA, the headquarters of American Optical since 1869, was closed in 2005. The only remaining manufacturing was glass executive bifocals which, due to manufacturing difficulties, were not relocated.

Under Mike McKeough’s leadership Adelaide, AU was closed in 2008? The products were transferred to Tijuana MX and OEF (Optical Electroforming), Tampa Florida. OEF was closed in 2005 with production, also being relocated to Tijuana, MX.

SOLA purchased two plants that manufactured polycarbonate finished lenses. Both were eventually closed.

- Neolens, Miami FL was closed in 2000.

- Oracle Lens, Warwick RI was closed in 2009.

Back Office Structure 1999 Onwards Jon Westover

John Bastian left SOLA Australia in 1998. In 1999 John Heine appointed Warwick Duthy to run SOLA Australia. It was rumoured that John Heine saw Warwick Duthy as his potential successor. Warwick got marketing and R&D and Jim Cox got Back Office, i.e. all the factories and supply chain and there were commercial GMs in each of the regions, namely Americas, Europe, Asia-Pacific. The Back Office leaders were Barry Packham strategy, John Westover Asia Pacific, Barry Weitzenberg Americas and Tony Donogan Europe.

Refer link for full details

Petaluma close

Following the ascension of Jeremy Bishop as CEO in April 2000 Barry Packham replaced Cox as head of back office, which became Global Operations. Barry and Jeremy made the decision to implement Barry’s “what-to-make-where” manufacturing strategy. In late 2000 Barry asked Jon Westover to relocate to Petaluma to close Petaluma. The initial plan, which was called project Columbia, was to migrate Spectralite and CR-39 to Mexico, but ended up migrating all products except metal mold manufacture and very small R&D capability. Project Columbia took 9 months to implement. The yield immediately before its closure was the highest in history of Petaluma. After Dave Provow left, Roy Miramontes was appointed plant manager and he, along with Sean Holt as project manager and Jon as overall leader, drove the whole agenda with some great work by all the locals. Vicki Villanueva was a key local. Lot of pride in that achievement.

In parallel with Project Columbia, Eldon, Missouri was closed by Steve Heilborn with the able assistance of Sharon Rotty. Eldon had made glass molds and glass lenses for many years. The mold and some lens products were migrated to Tijuana and the remaining glass lens products to IOSSA in France.

Manufacturing business unit, i.e. a Global Operations business unit (post SOLA)

Previously all Operations P&L were with the local identities. So the setting-up of a Global Operations business unit in 2005 was a very significant change as it had its P&L and balance sheet and the resources to drive that agenda. It was self contained with only two customers (1) all CZV Commercial Identities and (2) Transitions. It was not allowed to supply anyone else, i.e. not to third parties.

Initiatives included continuing on some of the themes started previously, e.g. continuing mass manufacturing cost reduction by closing some of the factories that should have been closed 5 years previously (Wexford, Oracle, IOSSA, SOLA Australia, Germany CR lens making and SOLA Miami Molds) with all production transferred into Brazil, Hungary (for Zeiss progressives out of Aalen), Tijuana Mexico (for glass from IOSSA France and for SF poly from Oracle) and to American Polylite in Taiwan (for FSV poly from Oracle).

Project Iceberg which was to close the original plant in Petropolis, Brazil was successfully completed. This was the same philosophy as Project Genesis (refer Mexico Manufacturing), namely to move all activity from the old plant 1 and consolidate in one decent factory.

All these initiatives led to big cost reductions, but was lot of work. Also at the same time Lean was started. It built on the Deming philosophy already in the self contained business units. The methodology adopted was to work with an external consultancy but having internal people as very capable lean champions in each site and with Rodolfo Moreno (Mexico) driving the whole Lean agenda globally. Lean started slowly but a very solid foundation that most sites have built on was laid.

Lean became very much part of the success. What we were doing was (1) the step change type improvements like migrating the entire high index from Lonsdale to China which had a massive labor cost saving and (2) the continuous improvement savings through Lean (elimination of waste, etc). Nick Middleton drove the technical support and the cost down agenda.

He was doing the big projects and Rodolfo drove Lean, continued the cultural change and the more incremental improvements.

The other key activity was the major work on supply chain; building on the work Barry Packham had started during his time, which was using MRP2 supply chain principles and the Oliver White Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) process.

The focus was to standardise the S&OP process across the regions, with demand planning, new product planning and supply planning managed in a monthly rhythm with a standardised approach across the world. At a more detailed level factory planning and scheduling processes were standardised and coordinated centrally, also mold planning.

North America as a region had a very well established S&OP process, the major drive at this time was to establish the identical process in other regions and through that approach provide the best commercial intelligence for Operations with which to drive and manage the global supply chain.

Working capital and Opex were reduced, distribution was optimised and high service performance (~97.5 to 98% level) enshrined to deliver the lenses that were required.

OBSERVATIONS ABOUT THE CULTURE OF THE COMPANY - 2001 ONWARDS Charlie Kunkel

I joined the company in September 2001 and soon realised the culture of the company was very unique and very special, which I did not appreciate at the time. I believe it was one of the secret sources for the success of the company.

When I joined the company I worked for Mark Turfler in the Corporate Finance Department for 2 years as part of the team transferring the headquarters from Menlo Park to San Diego. In 2003 I started working for Barry Packham and then Jon Westover in 2004 when the organization reverted back to a regional structure.

Global Operations

Restructuring and refinancing had already been done by the time I joined the company so the worst was already over. I imagine it was quite hard in those earlier days but after I started there were initiatives and hard tasks still to be done involving restructuring and bringing the company to financial stability. Project Rooster (refer section 4.3 Rooster) and the transfer of manufacturing from Petaluma to Mexico (refer section 4.3 Back Office Structure 1999 Onwards) were projects that Barry Packham and had already identified that still needed to be executed. When I became involved with Global Operations, I realised what a great leadership team the company had. I can say that about the company but very specifically about Global Operations. The expectations and demands from Barry Packham were very high but the team he had working for him (Jon Westover, Jorge Mario, Bob Sothman, Mike McKeough, Wilson Peng, Kym Gibbons and others) was such a close knit, strong team where everyone knew what had to be done. They worked very well together and were good at executing the required initiatives. They worked hard and played hard day and night. I believe the bond & trust must have been formed during the worst times and as they had some success the trust and closer working relations even improved.

The Corporate office was an interesting place to work, especially the international aspect. Every single day you had a British guy, a Mexican guy, a Brazilian guy or an Australian guy walking into the office. They knew what they had to do and just went ahead and did it. I would not describe the office as being fun because we had tasks and were highly focussed on achieving success under the leadership of Barry Packham.

G13

Another element created about that time was the G13/14 which was the company’s leadership group. The composition of the team changed over time but the core group included Jeremy Bishop, Barry Packham, Jorge Mario, Jon Westover, Gaetano Sciuto, Mark Ashcroft, Lorenzo Ungaro, David Cross, Paulo Frias, CFO (Ron Dutt or Steve Neil), Hubert Weiss, Paraic Begley, Michael Pittolo and John Rosser, i.e. the top 13 or 14 Operational and Commercial personal – they would meet every month at least telephonically and every 2 - 3 months would have a face-to-face meeting somewhere around the world. In 2004 David Cross was responsible for leading this group that was then focussed on looking for growth. This is after the restructuring and the company was more stabilized. I was the scribe for the G13 meetings and again this was a highly focussed group of senior leaders working very well together and was something else that contributed to the success of the company. I remember being in one project looking for a new progressive design with the product to be launched in 6 – 8 months. Mark Ashcroft, Steve Neil, Paraic Begley etc settled on SolaOne which is the best selling progressive design we have today 8 years after the launch. For me it was really interesting to see how closely the leadership team worked together even at such a high and cross-functional level.

It has been 6 years since the merger of SOLA/Zeiss so as I reflect back on that culture and the good blessings that I had to be involved with the likes of Barry Packham, Bob Sothman and John Westover. I learned a lot. Global Operations and the G13, that also involved the Commercial guys, had a very unique and special culture that I don’t think can be easily replicated. I think it was that culture and the willingness to work together that bought the company back from the brink. Efforts were consciously made to feed that type culture – I remember Jeremy saying “you knew how good the meeting was going to be the next day by the size of the bar bill at the end of the night”.

To summarize, the Global Operations and G13 teams worked hard and played hard; they loved being together, were very focussed and that is what contributed to a lot of the success that the company had.

CHINA

Norinco SOLA – Starting a Manufacturing Plant in China Gerry Loots

In 1981 a company in China owned by Norinco (Commercial Arm of the Red Army and a major Military Supplier) started to experiment in casting hard resin (CR-39) lenses.

In 1985 they sought assistance and acquired a used casting plant from the 3M Corporation which had purchased a company named Armorlite, which was a significant early producer of hard resin lenses.

3M was selling off the old Armorlite assets and the Chinese company purchased an outdated casting line.

After some basic training and the installation of the line in Xi’an in China the project failed because the technical instructions had been inadequate and as soon as the contract for support expired the Americans just left the site and discontinued any communication.

The production line turned out to be a complex process with a graduated temperature water-bath curing process and a mold cleaner that damaged too many molds in the process.

The principals of the lens casting site sought SOLA Hong Kong’s assistance and so started the relationship between SOLA and Norinco which led to a joint venture to produce stock prescription lenses in China for domestic sales and sunglass lenses for export sales.

The first serious exchange that occurred between Norinco and SOLA was when Gerry Loots visited Xi’an with Samson Lee and Stanley Lee from SOLA Hong Kong in January 1988 to determine if the people were capable of running and dealing with a SOLA technology production line. The results were favourable and the wheels were set in motion to negotiate a deal with the Chinese.

Loots, Roger Goodale and Chris Schutze spent a lot of time between Adelaide and Xi’an working through the requirements for a successful enterprise.

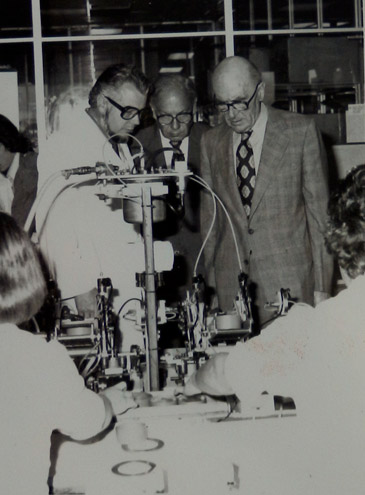

In August 1988, John Heine, CEO of SOLA and Owen Roe, Asian Regional Director, visited Xi’an and made the final decision to go ahead and establish a joint venture.

SOLA invested AU$3.5 million in equipment and intellectual property and Heine’s instructions were to make sure everything was done well and on time.

After that there were many more visits in 1988 by Loots, Roe, Goodale and Schutze with Hong Kong interpreters to determine the details of the agreement and the specification for the production facility.

It was decided that a production line would be built and commissioned in Taiwan and that it would then be moved to China.

A team of people was established to devote 100% of their time on the project. Gerry Loots was appointed Project Champion to be assisted by Roger Goodale who had been the SOLA R&D Manager for many years and Chris Schutze was appointed Project Manager. Randall Engel and Robert Berry were engineers and were charged with building the equipment and commissioning in Taiwan. Nick Middleton was made responsible for documenting the processes and training the Chinese which he would do during a planned technical secondment in Taiwan. From SOLA Taiwan, George Huang was given the role of technical link with the Chinese as he could communicate technically in Mandarin. As there was a large mold making requirement, Chan Ngai Kong the GM of SOLA Singapore, visited to give an opinion on requirements for improving the process the Chinese had inherited from the Armorlite project.

There was a lot of travel from Australia and Taiwan to China to fine tune the arrangements and make sure that the Chinese were keeping to schedule with their parts of the deal which included the construction of the production area inside an existing building

A major delay occurred when the infamous Tiananmen Square incident broke out in June 1989 and Roe and Lee had to leave China suddenly. The project was put on hold while the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs had China listed as an unsafe place to visit. Construction of the production line proceeded because it was deemed a low risk that the project would not continue. As soon as the travel bans were lifted the project was rejuvenated.

In early 1990 a great deal of work was done to try to find a General Manager but the costs were high and expatriate Chinese had very demanding requirements. Eventually Loots was offered the job and started to manage both sides over numerous visits.

In May 1990 a delegation of 12 Chinese chosen to manage and run the Xi’an plant came to Australia for a month for training and orientation at SOLA Optical Australia. Martin Flippance taught the financial requirements for reporting and Nick Middleton, Donna Whitehead and Paul Flude taught the processes.

After a SOLA Group wide search a “maintenance expert “ was identified at SOLA USA and he was offered a secondment which he accepted and thus Hart Ezell joined the team and transferred to Xi’an at the end of September.

In September the Loots family shifted to Xian to link with Middleton, Schutze and the Engineers charged with making and setting up the line.

The production line was completed and was on its way to Xi’an via Hong Kong and arrived as all the technical people arrived so there was no delay for the installation process.

On October 30 1990 the Xi’an Production Line was wired and fired up and the facility was set to go. Production started with molds and gaskets sourced from SOLA companies.

Donna Whitehead and Nick Middleton had completed the basic technical transfer on casting and line management and Flude taught sunglass lens tinting.

As the training developed a few other people were seconded in for specific reasons. Jim Mott came out of retirement in Adelaide to help with basic production management. The production manager at the Xian plant needed guidance to manage for maximum efficiency and Mott was the man for that role. As Nick Middleton left Mott took over from him.

Bernie Dunn joined the team to teach injection molding and stayed for a while to manage the plant.

On January 23rd 1991, about three years after the first serious visit by SOLA, the Norinco SOLA Joint Venture had it official Grand Opening Ceremony with lavish banquets and fireworks in freezing conditions.

There is no doubt that all involved found this project to be a great adventure.

Xi’an was a city of over 5 million people and a big military supply centre but SOLA’s partner company, The Chaoyang Optical Factory was a poor member of the Norinco Group and while the people were trying to do their best, the factory was never going to get to a standard that matched any other SOLA plant. SOLA had a state of the art casting and tinting line inside a badly fitted out factory in a very rustic ex-university campus and quite a way from the city centre.

Xi’an is best known in the West for its Terracotta Warriors exhibition which is truly magnificent. However, the city had only recently opened to Western travel and business ventures and had not modernised at the same rate as Beijing or Guangzhou, mainly due to its central location.

Some of the critical items which the Chinese had committed to supplying came in late and delayed full production. Injection molding tooling was over a month late and glass mold manufacture did not go smoothly because the Chinese had a different perception of the required quality standards so a technician from the Singapore mold making plant had to be seconded to get the process sorted.

The local people were not familiar with the Joint Venture Laws of China, which Loots and Roe had studied intently and they were very appreciative of the input the SOLA people gave on basic issues like pay structures and benefits and company structure. There is no doubt that every member of the start up crew was held in high esteem by the Chinese Partners and the local Norinco management team.

Every team member was treated like an expert and the Chinese accepted the training and guidance very well. And the western visitors respected their Chinese hosts and had a great deal of fun with the people, the language, the social events and the frustrations from working in a tough environment.

Three months before Loots’ tenure as General Manager was to end a search was started for his replacement and eventually Simon Lui was selected. Simon was a mainlander living in Hong Kong and understood the situation very well but could also see that the facility was of low standard and that there would be a lot of work to continue improvements. He eventually broadened his role in SOLA’s management team which was charged with development in China.

There continued to be technical exchanges with Xian and eventually Dr Bob Sothman visited to give his opinion and advice on improvement of the very dangerous initiator production process that the Chinese had established.

Eventually SOLA’s focus went to a new project in Guangzhou where a very large lens production facility was being built and the Xian Joint Venture paled into insignificance. But Xi’an was a building block in the end play of dealing in China. Many of the people involved in the project worked on the Guangzhou project.

SOLA learnt a great deal about dealing with the Chinese from the Xi’an experience. Owen Roe said that the project was in fact the fastest profit turning venture that SOLA had been involved with. It was a relatively small company but it started the ball rolling in the Chinese market and kick started SOLA’s Rx business on the mainland.

It was a true team effort and everybody involved worked hard and long and carried on that SOLA Spirit that makes sure that it just gets done.

SOLA China Manufacturing Kong Ng

By the early 1990’s, SOLA had two successful and profitable manufacturing plants in Greater China. One of those was SOLA Taiwan, and the other Norinco SOLA in Xi’an. The size and growth potential of the China market for plastic lenses were obvious, and the environment for foreign investment was getting better in China after years of economic reform.

While Norinco SOLA was profitable, it was a 50:50 joint venture. Management decisions were slow. Negotiations to expand the manufacturing capacity there, but with SOLA holding the majority share, did not lead to an acceptable outcome. By 1994, the Chinese Government further opened up the economy and allowed foreign companies to incorporate Wholly Owned Foreign Enterprises (WOFE). SOLA was now able to build a lens manufacturing plant without having a local joint venture partner. However, as China was still evolving her economic policies, her policies and way of doing things were unfamiliar to westerners. An investment company based in Hong Kong known to have investments and connections in China became an investor who not only provided much needed capital, shared risks, but also provided valuable advice on doing business in China.

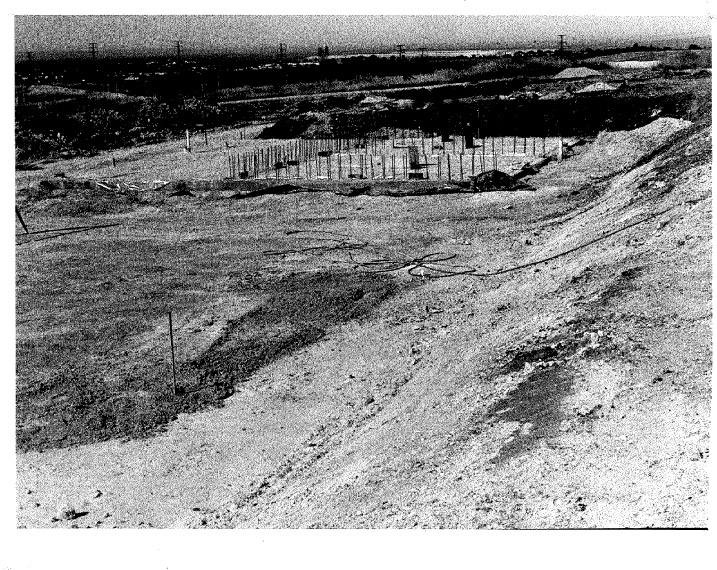

Simon Lui, who was GM of Norinco SOLA at the time, was moved out of the joint venture to head the new SOLA China. Finding a right location for the new plant took more than a year. Finally in late 1995, a piece of land was found in Jiufo, a small and poor village which had recently zoned some land for industrial use. Jiufo could not be further from anywhere. It sat in the northern city border of Guangzhou and was completely rural in characteristics. Surrounded by rice fields and lychee orchards, the village government had carved into a small earthen hill and used the earth from it to fill some ancient rice fields adjacent to a small, two-laned country road. It was linked by a narrow low grade road to the city. However, the National and Guangzhou governments had development plans and were implementing them at a great pace. By September 1996, forming part of National Highway #105, a four-lane highway had been built to link the city to Jiufo and beyond.

The Guangzhou China factory in 1998 and today ...

Project team – consultants; organization context

SOLA was organised regionally. Each regional office had responsibility for all the businesses within its region, covering manufacturing, Rx, sales and distribution. The SOLA Asia Regional Office (SARO) therefore had responsibility to implement the project to build this new lens manufacturing plant in Jiufo.

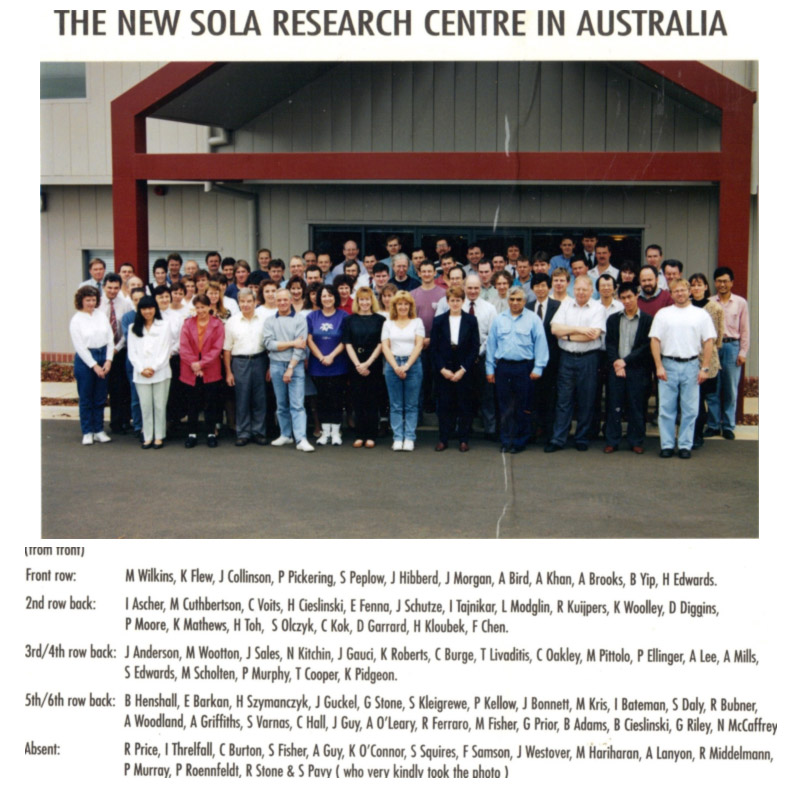

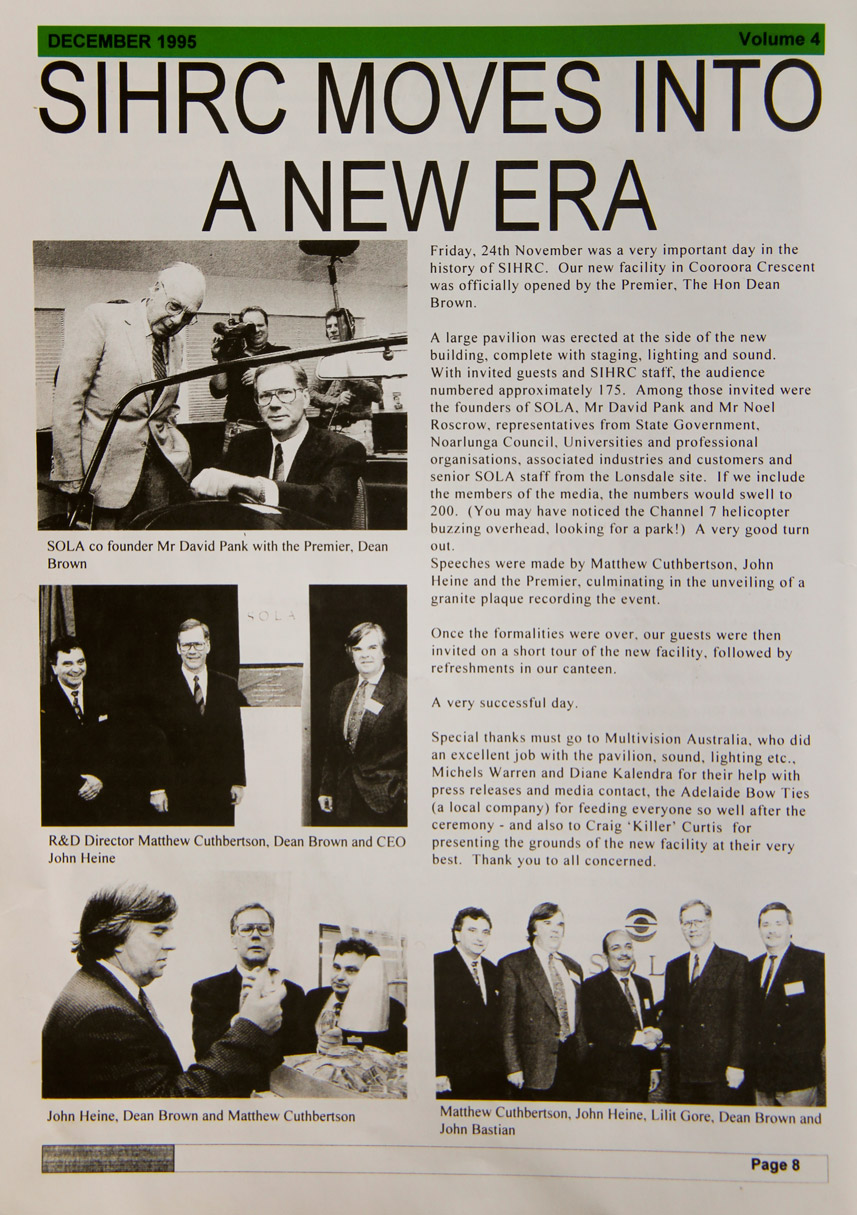

SARO picked two key people to lead the project: Brad Adrian was the Project Manager and Tony Linkson the Project Engineer. Brad had worked for some years in R&D, Lonsdale by that time, and Tony was an engineer of SOLA Australia’s manufacturing plant.

The project team was supported by Paradigm, an Adelaide based project management consultant. Woodhead, another Adelaide based engineering consulting firm, was commissioned to develop plant design options. A Hong Kong based engineering consulting firm, Rust PPK, was appointed to develop detailed engineering plans and to supervise a China based local design institute, the Guangzhou Petrochemical Engineering Design Institute (GPEDI), to convert those plans into ones that complied with China’s various construction related codes.

Kong Ng, who was recruited in September 1996, later became Project Director.

The project team reported to a steering committee consisting primarily of Barry Packham VP of GMD and Owen Roe, VP of SARO.

The project was dubbed the China Plant 2 Project.

Project approach – BDP, international input

Barry Packham had joined SOLA several years before the China Plant 2 Project was initiated. As head of GMD, he had lead the group’s manufacturing plants on a continuous improvement path, a key step of which was benchmarking. Through benchmarking of each production sub-process, the group’s best demonstrated practices (BDP) were catalogued. SOLA clearly knew which manufacturing plant in its group was the best at yield, productivity, and quality for each of the production sub-process, and the reasons why.

A key objective for the China Plant 2 was thus to implement BDP processes of the SOLA group. To ensure achievement of this objective, an international team of SOLA engineers and lens making practitioners was selected to specify equipment and process parameters for the plant. The team was assembled twice during the plant design phase. The first time was focused on process equipment and plant layout; while the second time was aimed at detailing production facilities and utilities.

As a result, various equipment, processes and technology transfers came from Australia, US, Mexico, Ireland and Taiwan.

One other very important consideration was in human resource planning and training. It was decided that the best of SOLA culture, skills and work practices would be imparted to the new work force of China Plant 2.

Challenges – import duty deadline, design impediments of local codes

As a new WOFE invested manufacturing plant, the Chinese Government policy allowed equipment to be imported with duty exemption. The deadline was 31 December 1996, after which all imported equipment would be subject to import duty and VAT, totalling up to about 40% of the imported value. All the equipment supply sites put in extraordinary efforts and beat the deadline. Just before the 31 December however, the government gave an extension! The equipment was delivered one year earlier than it was needed for installation.

Meanwhile, the plant design was being converted into detailed construction drawings by GPEDI. This was not at all a simple process. Construction costs were highly affected by detailed design and so had to be monitored closely. The most vexed issues were related to the strict interpretation of China’s construction codes pertaining to fire safety. As the lens making processes involves chemicals which were flammable and a few which may be explosive, the design of some of the rooms were going to be prohibitively expensive to build. To the credit of Tony Linkson, he was able to persuade the design institute’s engineers and relevant government officials to classify the risk to a lesser code level.

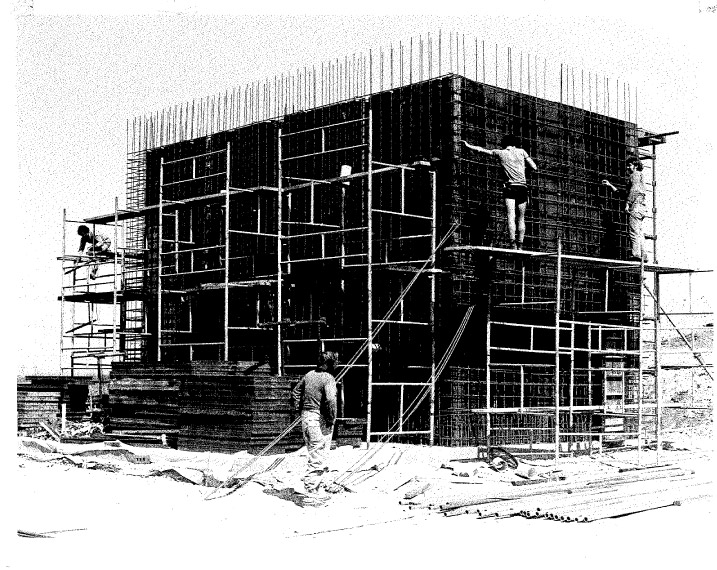

Building the plant – rain and mud

In the summer of 1996, Maoming Construction Company was awarded the construction contract for the plant and dormitory. Work started on site in June. Guangzhou’s summer months are hot and humid, and there are often rain storms. Autumns and winters are generally drier but not for the construction of Plant 2. The China Plant 2 was virtually built in the rain.

For such a big building, the construction period was only about 11 months. Piling works commenced in mid June, and the contractors handed over the site in stages starting from January 1997, and all building work was completed by May.

The dormitory was also handed over for use in stages, floor by floor.

Installation and commissioning – international support team

SOLA’s international team arrived to install equipment early in the new year of 1998. Starting from mid January, equipment was moved from their storage locations, after lying dormant for over a year, to be now put into the new plant.

The place was still a construction site. While some of the rooms of the main building were handed over to SOLA, the roads were not yet paved, and only temporary power and lighting were available. What ought to have been roads were muddy tracks. Equipment was transported in on heavy trucks. On one occasion, when an air compressor was being brought in, the truck started sinking into the mud. Forklift trucks were almost un-manoeuvrable. Luckily the SOLA engineers had a “never give up” attitude. They overcame one difficulty after another and completed the installation work, adhering to the project schedule.

Training the people – local and global

In parallel with the construction work, a local team of managers, engineers and operators were being assembled.

SOLA believed in localization of management. A key aspect of the project was therefore to build a local team that stood on its own and that required minimal expat support. At the same time, the local team must also be an integral part of the larger global family. A properly designed and executed human resource plan was of critical importance.

In addition to planning an organisation structure, much of the plan was focused on organisation culture.

Wilson Peng was recruited in November 1996 as the General Manager.

Training of the new recruits was given in different parts of the SOLA world to ensure learning of BDP techniques and operations, but also to ensure wide ranging bonding of key people.

A core group of 10 operators were sent to Petaluma for operator training in all areas of the production plant. These operators formed the seed group who then trained others within the China Plant 2.

Ramp-up

The first lens was cast in March 1998. Production was ramped up gradually, starting from a few hundred lenses a day. This was both to validate the production equipment and systems as well as to train the operators.

A couple of expat trainers, Hugh Tedmanson, Vicky Villanueva and Raelene Kuipers worked on the shop floor with the new operators for a total of 2 months. By the end of that period, the plant was making 10,000 lenses a day.

Click to download:

Growth Wilson Peng

From local market to global Market

Initially, SGJ was set up for Asia market, especially for China market. For various reasons, China could not sell products in a sustainable volume for SGJ. So we met a tough situation right after we started “mini” mass production, small volume (around 10 k dgc) but high inventory. It was my big concern during the period in 1998. It was luck that SGJ had been changed from local manufacturing to global as SOLA top management developed right strategy and made a timely decision in 1999. John Heine, CEO of SOLA, at the duck school in Miami in 1999, said: “Wilson, don’t worry about volume for SGJ, we will fill your hungry stomach (all capacity) and your plant will have expansion soon. You guys should make sure you can make it!” Since then, SOLA started production migration from Taiwan, US and other high cost counties to Mexico, China and Brazil under leadership of Barry Packham, Jon Westover, Michael Pittolo, Tony Donagan, Kong Ng, Bob Sothman, Nick Middleton, global technical support group etc.

- Casting volume from 10,000 daily gross cast to 90,000 daily gross cast

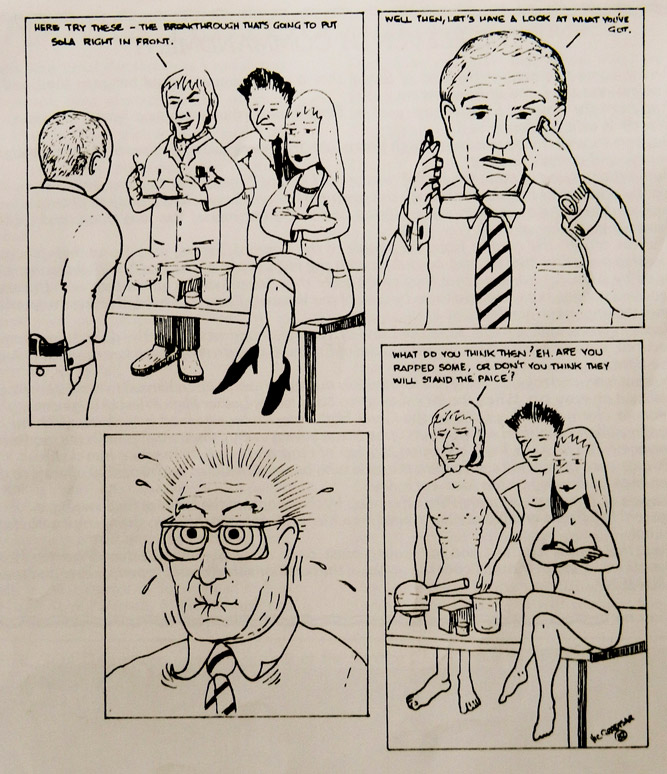

From 1999 to 2002, SGJ expanded its volume capacity of index 1.499 products from 10K DGC, 24K, 40K, 70K, 80K and 90K DGC. SGJ became the biggest casting plant in China in 2002. One remarkable story was we made an innovative breakthrough for the No. 3 production line. Except using two auto strip machine, the 3A and 3B line combine their heating/dry tunnel. The idea was mainly from Barry Dolan, Kong and other people in an innovative brainstorming with a cup of beer in a bar. Its layout has advantages of space and energy saving and looks like symbol of Chinese bronze money used in ancient time. So I said the line will bring good luck and get us make money soon. Since then, we received our first payment from US commercial and

- SGJ went from local to global supplier

Since 1999, SGJ started to supply its products gradually to China, Asia, Australia, North America, Europe etc. our unforgettable experience was to supply our products to AOF (American Optical France). AOF was very strict in their quality requirement. Initially, we argued each other on SIQ. AOF used AQL 0.65 when SOLA standard was 2.5 and it was very tough to pass their IQC. But we quickly realized that customer is king and got to understand what their real concern was. We passed their QC finally in half year by improving our product quality. We also invited people from AOF to do on-site audit and helped them build up confidence. Since then our products portfolio increased

- From uncoated products to different hard coating and Anti-reflecting coating products.

- Let’s grow up together

The management team and all employees have been growing while SGJ is growing its business since started its operation. SGJ has created very good cultural working environment while expanding our production. Factory, School and Family is the core value of SGJ. People working together are full of spirit, energy, friendship and fun.

Barry Packham, Kong Ng, Jon Westover, Michael Pittolo, Vicky, Nick Middleton and many other colleagues from all over counties worked with us like coach and we learnt a lot management skills and technical know-how from them. I personally was very lucky to get opportunities to attend the last batch of Duck School, a sharing program for people understand and respect to different culture and training program for people to learn leadership skills. I always remember the saying in the program: Take a risk. Make an action and pay the price if something wrong. It motivates us to make timely decision and make thing happen effectively.

Key locals that made a significant contribution:-

- Johnson Zhang, currently CNMA plant manager. In 1997, he was recruited from a joint-venture of Hilti located in Guangdong China, a well known Swiss company. He brought a training team of SGJ in Petaluma SOUSA plant. The team was called as seed team in the project and made great contribution in SGJ history since the first lens was made in 1998. Johnson was the production manager initially and promoted to be a production director then plant manager while he has been gaining a lot of production experiences and management skills.

- Allon Zeng, he was also recruited in 1997 but started as process engineer. There was a nice story about Allon. We found everything was qualified except his English during the interview as he used to work for a Japanese company in Guangzhou. We were not confident if he could manage his job with his very limited English. And it was critical as he was the first process Engineer and had to communicate with our global support team. Therefore we told him that we will put him in a waiting list and see if he can improve his English in a reasonable level in certain time. Three months late, he was working very well with his spoken English. While expanding SGJ production, he was gradually promoted to chief engineer, technical director and now the plant manager of CNRX, the second biggest Rx Lab in CZV now. He is leading his Rx Lab and working together with local team and global support team with his sound English now.

- Nancy Zhao used to be the GM secretary and she is the senior HR manager in China now. She has been playing very important role in developing cultural working environment and practicing the core value of family and school in SGJ.

- Rick You used to be a process assistant engineer and he is the senior manager of high index production plant now, an advanced production line in CZV.

- Leon Liang used to be one of the seed team and received the comprehensive training in SOUSA. He has been a hard worker and skilful in self-learning. So he always a pioneer in his peers and promoted to be production shift lead, supervisor, manager.

- Nancy, Rick, Leon and other people like York Tian, Jason Lv, Jaline Li etc. are the best examples that the well educated and young generation could adapt SOLA value and take important role successfully. They have very high loyalty to the company and they are the future for CZV in China.

- Winston Yang, the plant manager of a newly set up RX Lab called global lab #5 (G5) in Guangzhou. He used to be a manager of “factory within factory” in SGJ. This approach was initiated by Jon Westover and we trained and got several very capable senior managers for China operations. Winston is one the people who left SGJ for a while but came back once he realized SOLA/CZV is the best work place for his and offering great opportunities in his career development. Carman He, the HR manager of CNRX G1 is the other one who came back to work CZV for us again.

- Roger Zhao, Jane Jiang, Edward Gu, Yong Jiang, Tong Xie etc. used to work in SGJ and made great contribution and are working for other international companies as General manager, CFO, CPO, directors and managers. The factory as a schools has been contributing a lot management and technical talents for SOLA/CZV and sociality in China.

Some more early photos:

| Click on images to enlarge: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SGJ/CNMA Milestones

| Nov. 19, 1995 | The agreement on buying the land was signed by CNMA and the Foreign Trade and Economy Commission of Baiyun District, Guangzhou city. |

| Aug. 20th, 1996 | The ceremony for laying foundation stone. |

| Jun. 27th, 1997 | Started construction of SGJ factory. |

| Nov. 1997 | Assigned three groups of managerial and technical staffs to be trained in USA, Ireland and Australia brother companies. |

| Jan. 16th, 1998 | First lot of imported equipment arrived at the Plant. |

| Jan. 18th, 1998 | First group of overseas technicians of SOLA arrived in Guangzhou for equipment installation. |

| Feb. 19th, 1998 | First batch of lenses and gaskets were made in CNMA |

| Apr. 20th, 1998 | CNMA operated. |

| Apr. 28th, 1998 | The casting yield up to 90% first time. |

| Aug. 6th, 1998 | First batch of hard coating lenses were made. |

| Aug. 21st, 1998 | Accounting system (Software UF-SOFT) passed the evaluation by Financial Bureau of Guangzhou |

| Aug. 24th, 1998 | Daily production volume arrived 10K pieces. |

| Sep. 1998 | Actual cost of hard coated lenses met standard cost. |

| Oct. 1998 | Shift production volume arrived 10K. |

| Oct. 8th, 1998 | SGJ opening ceremony. Mr. John Heine, National ....Spectacles Association representatives, local governors, and customs ....representatives attended the ceremony. |

| Oct. 8th, 1998 | First batch of AR-coated lenses made by sub-contractor in SGJ |

| Nov. 6th, 1998 | First packing line for semi-finish products installed. |

| Nov. 10th, 1998 | First batch of semi-finish lenses made. |

| Nov. 26th, 1998 | First batch of flat-top bifocal lenses made. |

| May 29th, 1999 | Centre Rx laboratory moved to SGJ. |

| Jul. 19th, 1999 | First batch of semi-finish lenses (14,720 pairs), and first batch of finished lenses (17051.5 pairs) exported to US. |

| Aug. 29th, 1999 | The shift production of semi-finished lenses arrived 8695 pieces. |

| Mar. 2000 | 1st expansion project finished, and SGJ capacity expanded to 24K pieces per day. |

| July 2000 | 2nd expansion project finished, by which SGJ capacity expanded to 40K pieces per day. |

| May 2002 | 6 more injection machines were installed. |

| Jul. to Oct. 2000 | 3rd expansion project and capacity achieved 55K from 40K pieces per day. |

| Sep. 10th, 2000 | Line 3A and Line 3B passed trial running. |

| Nov. 2000 – Apr. 2001 | SGJ capacity continued to expand, and topped 70K pieces per day. |

| Oct. 2000 | CNMA entitled as the Advanced Technology Enterprise of Guangzhou. |

| Dec. 2000 | First batch of 65mm stock lenses produced. |

| Dec. 2000 | First bevelling machine installed. |

| Dec. 2000 | Slight-way shelf applied at gaskets store. |

| Mar. 2001 | Automatic-packaging machine installed. |

| Apr. 2001 | Expansion project for 80K capacity commenced. |

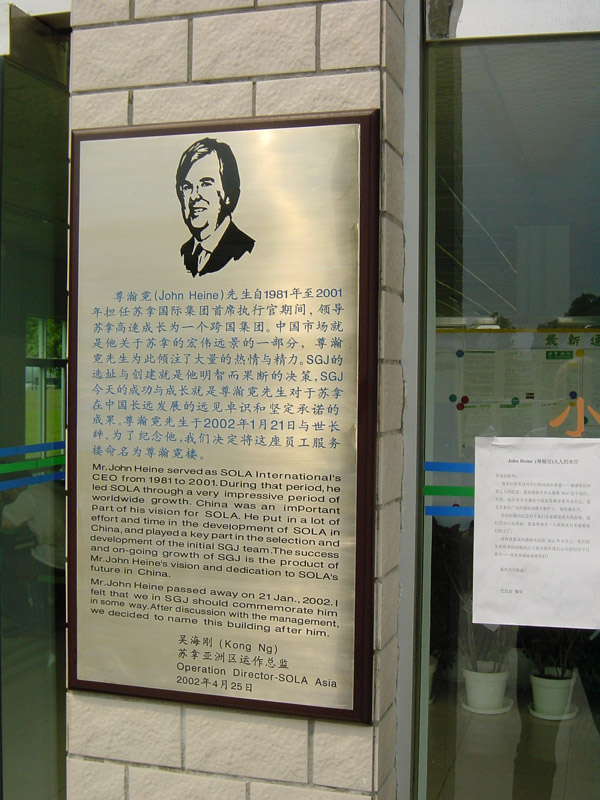

| Jul. 30th, 2001 | CNMA’s Service Building, John Heine Building, put into use. |

| Dec. 2001 | The first Spin-Coating line installed. |

| Feb. 2002 | Launched U8 (User Friend, a ERP System) Project. |

| Mar. 19th, 2002 | Launched “90 and 90” Project, means using US 90 cents per piece CR-39 uncoated lens by making 90K dgc. |

| Apr. 10th, 2002 | After-hours Training of Open and Shut was held. |

| Apr. 15th, 2002 | AR-Coating line installed, which was owned by SGJ. |

| Jun. 2002 | Launched QEHS project. |

| Jul. 15th, 2002 | The DGC increased from 60K to 68K |

| Aug. 2002 | Initiated “Get back to basic” project |

| Sep. 2002 | EVA material was used for S/L gasket production |

| Sep. 3rd, 2002 | CNMA topped 90% in its yield of Spin-coating |

| Oct. 15th, 2002 | AR Coating line trial production commenced |

| Nov. 2002 | One ultrasonic machine added to DIP-Coating line |

| Dec. 9th, 2002 | Plus lens migrated from OSM was first time made in CNMA |

| Dec. 28th,2002 | CNMA topped US$10 million on its exportation |

| Jan. 31st 2003 | “Voice of spring” visitor group visited CNMA (Including Mr. Jeremy Bishop- …………………………………………………CEO, Mr. Barry Packham-EVP, Mr. David Cross-CFO, and Mr. Mark Ashcroft-……………………………………………….. VP, Marking) |

| Jun. 2003 | Obtained a certificate of operating an Integrated Management System which complies with the requirements of BS EN ISO9001:2000, BS EN ISO14001:1996 and OHSAS18001:1999. |

| Jul. 2003 | Official implementation of U8 Financial Module |

| Sep. 2003 | Official implementation of U8 Production Module |

| Sep. 1st 2004 | Software design of Shop Floor Control System began |

| Sep. 20th 2004 | Naissance of MC (myopia control) in SGJ. At 9:30am |

| Feb. 2005 | SGZ became a group member of China Optical Association. |

| Mar. 22nd 2005 | Merger between the Carl Zeiss Ophthalmic Lens Division and SOLA International Inc. completed. |

| Apr. 21st. 2005 | Vice mayor of Guangzhou and other governors visited SGJ |

| Oct. 28th 2005 | CNMA launched 1.67 stock lens production ceremony Carl Zeiss Vision (China) Ltd was effected from Feb 22nd |

| Feb. 2006 | Mold BDP Meeting at CNMA |

| Jul. 2006 | CNMA joined The Multinational Corporation Club of Guangzhou as a key member |

| Aug. 2006 | CNMA launched first EFQM Business Excellence Assessment |

| Sep. 2006 | Asia Pacific executive meeting held in Shenzhen |

| Sep. 2006 | Global operation and planning meeting held in Guangzhou |

| Apr. 2007 | AR Coating Extension project successes, and Teflon sales to the world market |

| Apr. 2007 | Launch Performance Evaluation Management System at production Dept. and soon extend to the whole company |

| 2007年7月 | Promote Think One Team concept throughout CNMA |

| Sep. 2007 | 3rd time to win the title of “Technology Advanced Company’ Reorganization from China Government. |

| Apr. 2008 | Established TPM (Total Preventive Maintenance) |

| Apr. 2008 | Promote Visualized through the whole plant |

| May. 2008 | Finished 1.56 Teflon project, and begin mass manufacturing |

| Jun. 2008 | Launched One Piece Flow project |

| Aug. 2008 | Finished establishment of the Andon System |

| Sep. 2009 | Finished Myovision project, with productivity of 1.5pairs/month |

| Sep. 2009 | Launched new product PC Teflon, 20k-30kpcs/month |

| Sep. 2009 | Developed a new product, AO Fresh 1.499, 1.56 and 1.6 -60k pcs/month |

| 6th Oct. 2009 | Launched SAP |

| 2009年11月 | Launched 2nd phase Hi-index project with capacity of 15K pcs |

| Dec. 2009 | Two new Leybold Syrus 3 coaters set up by end of December |

| 1st Mar. 2010 | Launched PEM E-System |

Tony Linkson’s China Story

My journey commenced in March 1996 when a meeting was held in Hong Kong and Guangzhou to discuss the supply of equipment to the factory. This was chaired by Barry Packham and Bob Sothman and attendees were there from SOUSA, SADC, SARO and SIHRC. By this stage, the main details of who was supplying what equipment had been finalised, it was a matter of coordinating timelines as the belief was that there was a duty free window to import equipment into China that was to close on Dec 31st 1996, a full 15 months ahead of the planned factory opening.

Soon after I started working on China Plant 2, John Bastian informed me that he was looking at opening a factory in Aurangabad India about 200km due east of Mumbai. By then I was already committed to China and I don’t know what ever came of this idea?

A significant amount of work had already gone into specifying what our new greenfields factory should look like and what equipment was to be used.

The first decision was that all products were to use sidefill gaskets and be made to the new standard hardness. The monomer mixing equipment and ovens including all of the control systems were made in Ireland using chilled water radiators to control the oven temperatures. All of the filling and stripping equipment was made in Australia with the screw brush washers out of Mexico. All of the trays and trolleys and OSI benches also came from Mexico. The data collection systems were from Australia. The packaging line including the flat edging equipment also came from Ireland.

My first task on arrival was to work with Derek and Weldon Ma to find somewhere suitable to safely store all of our major equipment for the next 12 months and then get the equipment imported into the country and delivered to site. We eventually settled on a government bonded warehouse used to store tobacco and TV sets. We were quite confident that the other products would be much more attractive to a would be thief.

The first 12 months were spent working at the World Trade Centre office in downtown Guangzhou. During this time we started working on “Room Data Sheets” for every room in the new factory. These sheets became our absolute bible on the requirements for power/air/water/drainage/lighting/ventilation/data connections. Once we had these in good order, we worked on the room layouts and how we would fit things onto the site.

Then there was the site itself. It consisted of land that had been partly dug out from the side of a hill and had a small creek running diagonally across the entire block. The creek came from a lake a km or so back behind the site. There was a small road in front with a kind of flood plain on our side of the road and a large river on the other side of the road. (This road eventually became a 4 lane highway.) I had both the creek and the river tested for pollution levels and found they were highly acidic, which was good because if we had any issues with our waste, it would be alkaline.

This small creek became a big problem. It had to be re-routed and the easiest thing would be to let it run into the flood plain in front of our site; however our neighbouring farmers wanted it to still flow directly to their properties. The solution was to then make a concrete channel along our boundary wall that then did a right angle turn across the front of the site like a moat and then kept going like a raised aqueduct above the floodplain for about 100m past our boundary.

The building design began with an initial plan from an Adelaide engineering firm. Our understanding was however that if we wanted to use a foreign design, we would still have to pay a fee to the local government equal to the cost of having the building designed locally. The other problem was that local constructions were almost all concrete buildings. They had almost no experience of steel structures and likewise Australian engineers would have very little experience with all concrete buildings. (Ironic that now China is a world leader in structural steel building fabrication).

So we ended up with Guangdong Petroleum Engineering Design Institute GPEDI and Engineer Li based in a100 year old French office block in part of the historic zone on Shamian Island originally built as a foreign trade zone for the British opium dealers.

We also employed RustPPK from Hong Kong to supply us with a site manager and a small team of electrical, mechanical, civil and architectural professionals that we could use as support to work with GPEDI on the designs.

For the majority of the next 12 months, Brad and I would spend 2-3 days a week either meeting with GPEDI or with Rust in Hong Kong. We also had great support from Roger Johns, a semi retired structural engineer from Adelaide who spent a large amount of time with us in Guangzhou.

I have great memories of arguing the most menial of things for hours on end with Mr Li. The worst thing was getting towards 12 midday with no resolution to the latest problem. As soon as midday hit, all of the GPEDI would disappear for a quick lunch and then turn all the lights out and go to sleep on the desks until 2.30PM!!! We would have to go have a bit of lunch, go for a walk and await the return of the team.

My most memorable discussion involved the demand from GPEDI, that the whole OSI room had to be made explosion proof and any windows would basically need to be bullet proof. This was due to the fact that Acetone was to be used, and they had a book that listed this as a dangerous highly flammable material. This was of course correct to a point; however international electrical standards, to which they were supposed to follow, sensibly worked on a zone of effect rather than a blanket rule. Eventually, I asked Mr Li if he were to design a football stadium with a roof, and discovered that there was a plan to hold 1ml of Acetone inside the stadium, would you need to make the whole stadium explosion proof. I knew we may be in trouble after he considered this for a few seconds and then said YES!!

Possibly even more amazing was the solution to this impasse. If we could get the Government fire chief to agree with a change of rating for the room, then it would be OK. Unfortunately the fire chief was actually a very high ranking military official who would not make appointments and worked in a building were foreigners like me could never enter. So, Wilson and Kong basically stalked him out and ambushed him one morning coming into his building. They were able to explain the situation and get the final seal of approval.

We eventually finished the design and had it costed, only to find that it was way over budget. I can’t actually recall now what we did, but in about 2 weeks we rehashed a lot of the design to finish up with the final layout.

There were a number of features that we included that did cost a bit more but resulted in a much better end result. Some of these included:

- OSI room had it own air treatment and filtering plant giving a near clean room environment.

- Terrazzo style flooring for all the monomer wet areas. This was something from SOLA Venezuela that would initially appear to be unlikely to result in a less slippery floor, but actually works.

- Workflow of the layout such that the whole process flows linearly from monomer mixing, to filling, to ovens, to stripping to OSI, to postcure, to edging, to packing and to distribution. All of the ancillary items were then placed adjacent such as compressors, injection moulding, mould store and AR coating.

- One single corridor separating the workflow areas from the ancillary areas. This corridor then acts as an easy accessible drain as well as a simple area to run power, air and water lines.

- We had our own diesel fired power plant. Included on each genset was a heat recovery unit. We included a pump and set of pipes to pump water through and take the heat from one end of the plant, all the way to the dorms, ensuring the workers all had hot water available, basically free from the gensets.

- We paid particular attention to the waste water treatment plant. This had to not only handle all of the industrial waste, but also all of the domestic waste. Eventually everything then found its way into the river across the road. I was always confident that our waste was to be far cleaner than the water in the river and would meet all of our own Australian standards.

So finally around June 2007, the design was completed, the tenders had gone out and Maoming was chosen as the main contractor. After a small ceremony, the site was established, and a small hut was installed in the paddock out the back of where the plant would go. This was to be my office for the next year.

Over the next 6 months, the concrete building slowly began to take shape. There were hundreds of people living and working on site. There were surprisingly few issues that arose from the design, the worst being a fire main being located such that it came up through the floor in the main corridor. We sorted this one out pretty easily and kept forging ahead.

I have written about the funny times we had during Jan/Feb 1998 in the old China Update. Basically once we got through our first lenses in March, we were able to finish up and leave China in June 1998 – a great time had by all, and I believe a great result was achieved by all.

Barry Dolan’s China Story

The start up of the new factory in Guangzhou was a significant milestone for SOLA for a great many reasons many of which will be highlighted by other contributors to this document. In my opinion, the direct involvement of so many people from all the other SOLA sites during the planning and implementation stages of the project was also a very significant event. In the past, a new factory start up would usually be supported by people from one site only. I believe that this unique approach has worked very well for SOLA. As a result of this approach, the new China factory is currently very well equipped with the best available process technology. The Chinese managers and engineers have also developed good working relationships with a wide range of experienced people from the more developed Sola sites throughout the world and consequently can avail of advice and support from these sites as required. Good friendships and a great deal of goodwill has also developed between SOLA China and the various people involved from the developed sites.

At the earlier stages of the project, SOLA Regional Office had successfully lobbied for support from the various established and developed sites. Each of the sites provided at least one person to assist SARO with the project and to co-ordinate the future support efforts of that particular site. I was asked by the general manager of SOLA Ireland to co-ordinate the efforts of SOLA Ireland. Following a series of meetings and discussions, each of the sites was asked to manufacture and install a specific range of process equipment and also to provide all the training and support that would be required. SOLA Ireland provided the curing ovens, monomer mixing and stock lens packaging equipment. All of this equipment was manufactured in Ireland using local suppliers and contractors.

The people in SOLA Ireland took a great interest in the China project. One of the first things we did was to put a notice up on the board asking for volunteers to travel to China to support the project. We were amazed with the response! Up to sixty people from the various departments had offered their services. Many of these people helped to collect and disseminate a vast amount of information which was needed at the planning stages, however only three employees actually travelled to China to support the project as part of the SADC support team. These three people were accompanied by three industrial contractors from Wexford and also Rodolfo Moreno from Sola Mexico. Sola Mexico had undertaken to commission the oven controllers and to provide training on site.

The most memorable part of the project for the SOLA Ireland people was the installation work on site in China and the training programs provided in China and Ireland. This was no ordinary project. This project was different because of the cultural diversity and the extra challenge that that presents. I think that many lessons have been learned and that many people who were involved with the project to date have become much more adept at cross cultural communication and have become much wiser from the experience. This type of project makes us clearly aware that we are all foreigners when we leave the boundaries of our own country and to be more effective we need to spend more time learning about the habits, customs and culture of the country that we visit. A wise man once said that we do not negate or reject our own culture by learning about someone else’s.

When we were installing equipment on site in China in February 1998, we encountered many challenges as one might expect given a project of this size. The biggest challenge we had was getting the equipment unloaded from fifteen forty foot containers and moving it into the factory. At that time of the year the weather was bad and the unfinished roads outside the factory were very mucky. Because of this we had great difficulty moving the heavy equipment. The problem was compounded by the unavailability of labour due to the Chinese New Year holiday. Tony Linkson, Hart Enzel and myself had to physically move all the equipment ourselves and at times we felt that we were doing a horse out of a job. We really looked forward to getting back to the hotel each evening to get out of our mucky clothes and to have a few beers; however the staff at the hotel were less enthusiastic about our arrival due to the mucky footprints on their expensive carpets. About a week later the rest of the team arrived from the various sites to install the equipment. Installing and commissioning the equipment in the relative comfort of the factory building was by comparison a very easy task.

It wasn’t all hard work; we did manage to find time for some multicultural socialising and enjoying the many good Chinese restaurants in the area. After the Chinese hotpot, Irish stew will never be the same again for the Irish contingent. The favourite pastime of the Irish lads after eating and drinking and watching football on satellite TV was walking and sightseeing. I believe they walked the length and breadth of Guangzhou at weekends taking in the sights and looking for bargains. Pat Dooley, one of the more experienced and well travelled Irish lads was also determined to teach the ancient Gaelic game of hurling to some of the local Chinese workmen. He even managed to persuade a local carpenter to manufacture the traditional wooden hurling stick; however I think that it’s fair to say that the Chinese lads were not terribly impressed and that hurling will never really replace table tennis in China. Pat then threatened to inflict the game on the Australian contingent; however he changed his mind fairly quickly when he remembered what they did to Gaelic football. He felt that hurling with an oval ball would never really catch on. Pat Dooley enjoyed working in China and he did not take too much persuasion to pay a return visit in June.

In October 1998, I returned to China to carry out some small modifications to the monomer mixing line and I was really very impressed with the overall progress that has been made since my last visit in February. I was also very impressed with the organisation and the commitment of the people and I am convinced that the project will be a great long term success. I felt very privileged and very proud to have been involved with such a worthwhile project. On behalf of myself, Rodolfo Moreno and the other support personnel from SOLA Ireland, I would like to extend our very best wishes for the future to our many friends in SOLA China. We were very happy to be involved with the initial start up of SOLA China and will always maintain a very close interest in the future development of the company.

MEXICO MANUFACTURING Jon Westover

Manufacture in Tijuana, Mexico

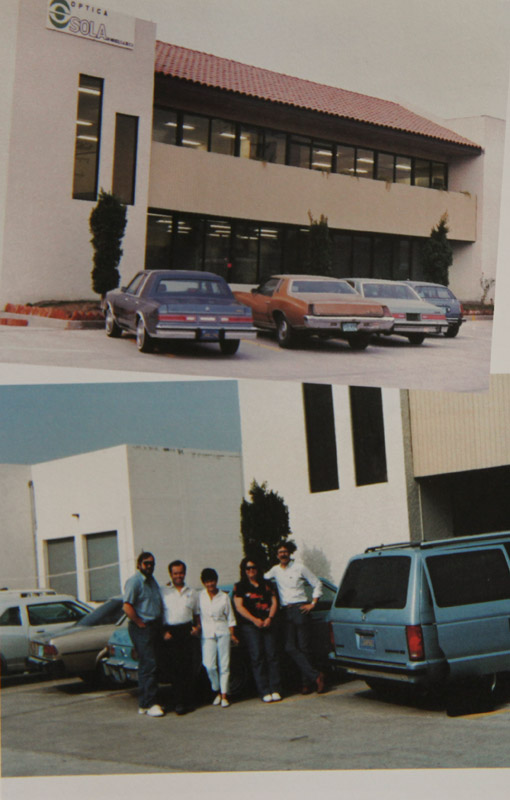

The decision to set-up manufacture in Tijuana, just over the USA border turned out to be a very successful one as it allowed significant sales increase in the USA. The factory was set up largely by SOLA USA and expertly run by Alejandro Flores. At one point in time (early 2001) SOLA Mexico was the biggest lens factory in the world producing up to 220,000 ophthalmic lenses/day. It made 14,000 different skus, comprising CR-39, Transitions, Spectralite and polycarbonate. A summary of the first 25 years is available here.

A brief summary of key dates:

| Year | Events |

|---|---|

| 1985 | SOLA (OSM) begins operation in Tijuana, Mexico. Starts with only 37 employees, one building and production of 5.5K lenses per day. |

| 1986 | Due to production increase the second (evening) shift needs to be opened. The first molding machine is installed and produces the first package in the month of July. |

| 1987 | The installed capacity is duplicated. The building in the company changes from 1 to 2 buildings. |

| 1988 | In this year we increase the land surface to 3 buildings with 4 production lines. The development of OSM increases by 50% compared to the previous year. |

| 1989-1993 | The following years are of continuous growth of the company, producing 100K lenses per day. |

| 1994 | The new facility OSM II is inaugurated by the Governor of the State. The Genesis Project takes place. |

| 1995 | SOLA celebrates 10 years in the industry with a Mexican Cowboy Fiesta. |

| 1997-2000 | The following years the company increases in people and production. In the summer of 2000 the company celebrates 15 Years with all the people in the premises of the new ...facility |

| 2004 | By the end of this year AO/SOLA merges with Carl Zeiss. |

| 2005 | The company celebrates its 20th anniversary with a Mexican Themed Fiesta |

| 2008 | The MXRx (Lab) begins operations. |

| 2009 | Lean Model is implemented In July MXRx accomplishes 1.5K lenses per day. |

| 2010 | MXMO (mold making) relocates and integrates with MXMA (manufacturing). In May MXRx achieves the CZV two star accreditation. In July MXRx increases to 6K lenses per day. |

After Alejandro retired, Jon Westover and then Jorge Mario ran the facility which is now back under Mexican management with Rodolfo Rubio in control. Mexico continues to be the major plastic lens manufacturing facility in CZV as well as now being the key mold making and glass lens site. Additionally it has provided a very effective platform for the establishment of one of CZVs high volume Rx laboratories, guaranteeing the future of the site for many years to come.

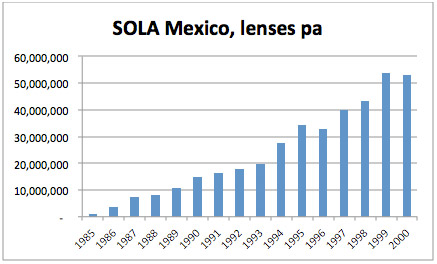

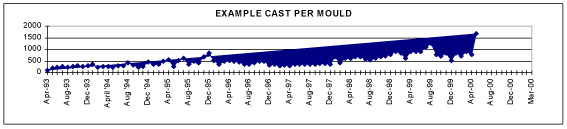

The growth in the SOLA Mexico operation up to 2000 is illustrated in the following graph:-

Mexico reconfiguration

However Mexico was not always a star performer. Key issues in 2001 were:-

- Systems and organization development lagged growth in volume and complexity

- Petaluma closure reduced support

- Customer base increasing in complexity

- Product quality lagging market requirements

- Increasing demands for flexibility and service

In 2001, Jon Westover was asked to transfer to Mexico. Thus the three ex-pats supporting that activity were Jon, Bob Sothman and Mike Pittolo.

The big project then was Project Genesis which was to close the original lens factory at Otay and move production to the newer factory at Isurgentes (which was still in Tijuana but south of the Otay facility) and the molds to the ex-AO Otay glass plant.

At the same time, a modern business structure (basically the same structure that had worked so well in SOLA Australia) with product focus factory units with total control plus a service unit supporting each one of those teams was created. Four manufacturing business units were created, namely Polycarbonate (leader Edgar Gudino), Spectralite (leader Aretha Bethancourt), CR-39 FSV + a little SF (Cesar Peralta) and CR-39 SF (leader Hector Rosales) along with a service business unit that did injection molding of gaskets and monomer preparation. A brief summary of Mexico in 2006 is available here.

In parallel, Jeremy Bishop decided to dramatically increase polycarbonate capacity and capabilities so Oracle was purchased in late 1999 and capacity expanded in Mexico with a total of 10 new and ex-Petaluma automods and supermods which were the unique pieces of equipment developed in Petaluma for making excellent quality SF blanks. This resulted in a dramatic increase in the volume capability for SF and FSV up to 30k dgc. This turned out to be a very brilliant strategic decision by Jeremy to invest in capacity and then go after the business.

High Index was a contrast as SOLA had been slow and did not invest in enough capacity so it was always chasing and never leading. Whereas with poly SOLA was the market leader due to proactively taking the decision to invest in capacity before it had the demand.

Some of the reasons for the big turnaround in Mexico were:-

- exiting incapable leaders who were not leading relying too much on their friends and mates and alignment with le patron

- much more metrics

- much more kpi driven decisions

- Deming philosophy

- using a much more data orientated and reporting methodology

- promoted young people with capability (and most stepped up)

With help from Mike Pittolo, Bob Sothman and Kym Gibbons, the team went from a weak spot in SOLA manufacturing to being the main engine for Global Operations for many years, delivering millions of $s to the bottom line, with reliable service and cost reduction.....

Key moves following Jon’s departure were the appointment of Jorge Mario and then Rodolfo Rubio. SOLA could not find anyone externally with the right skill set to take over the leadership role from Jon so Jorge Mario from Brazil was appointed. When Jorge was in that role, Rodolfo Rubio was recruited as plant manager initially, with the ultimate aim to take over from Jorge Mario. After ~ two years Rodolfo understood the challenges and demands of the role and was able to take over after Jorge left.

The overall aim in Mexico was to have an integrated Manufacturing Rx facility in Mexico - not cast to Rx - but to move from having a dedicated stock for Rx to one with lenses going straight from Mass manufacturing to Rx. This is now in place.

Some achievements during Jorge Mario’s time included:-

- Genesis, 2003

- Enclose lines/start Lean Concept

- Achievement of highest level in Safety and Work Environment in Mexico

- WIP reduction

- Back Order reduction

- Quality improvement

- New products site: Poly FT

- Improve capacity/quality and productivity in Poly, bar code/more press by machine/new back curve

- Continuous Improvement Teams

- New NS60 catalyst store

- Leasing contract with landlord for 15 years

- New organization structure- Rodolfo Rubio, etc

- Housekeeping - Internal and External

- Motivational activities, majority as Brazil

SOLA BRAZIL

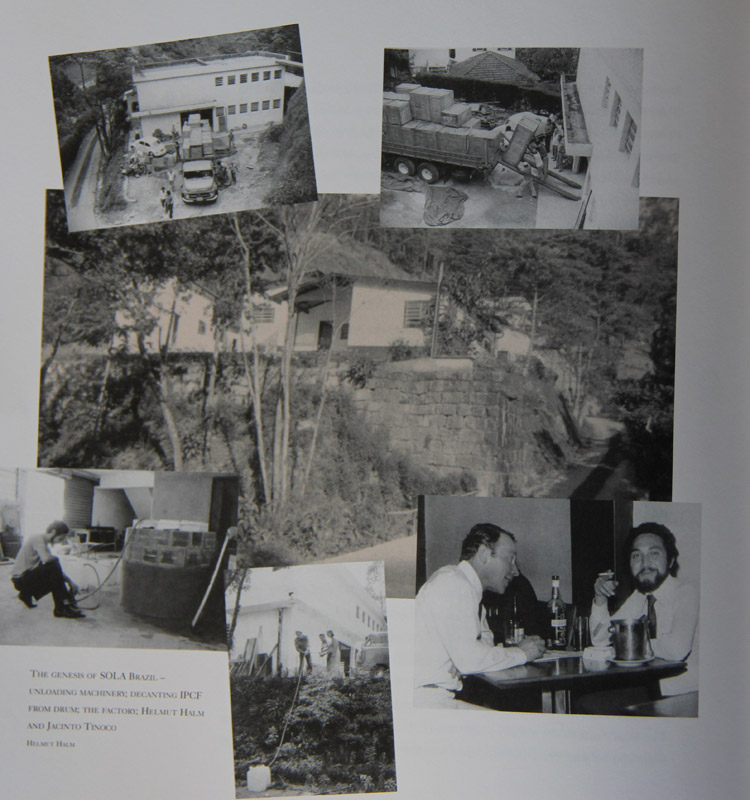

The Early Days (1970 to 1998) Bob Jose

The history of SOLA Brazil is really a story of its own, and it is not surprising that there was not sufficient integration with the rest of the SOLA story for more detail to be included in the original history published by Rob Linn.

Brazilian Ambassador visit 1

Brazilian Ambassador visit 2

Brazilian Ambassador visit 3