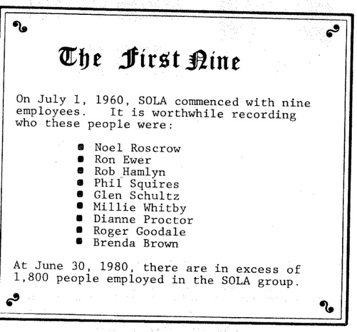

4.10 The SOLA Culture and People

The SOLA Culture

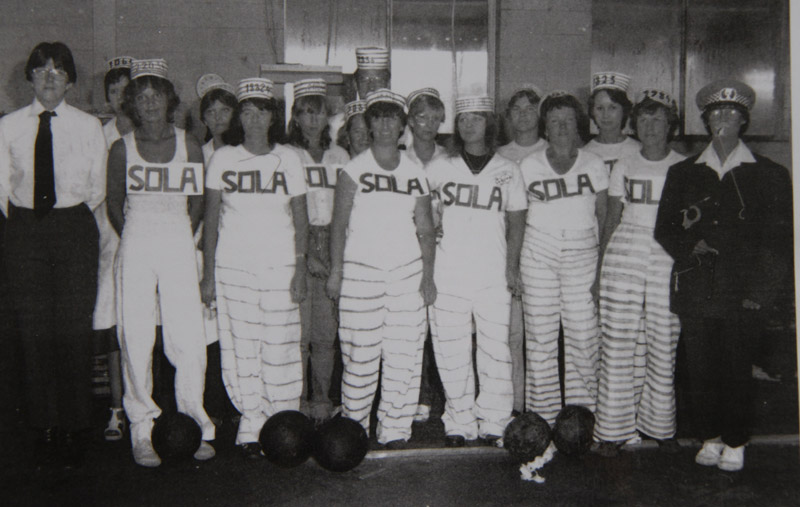

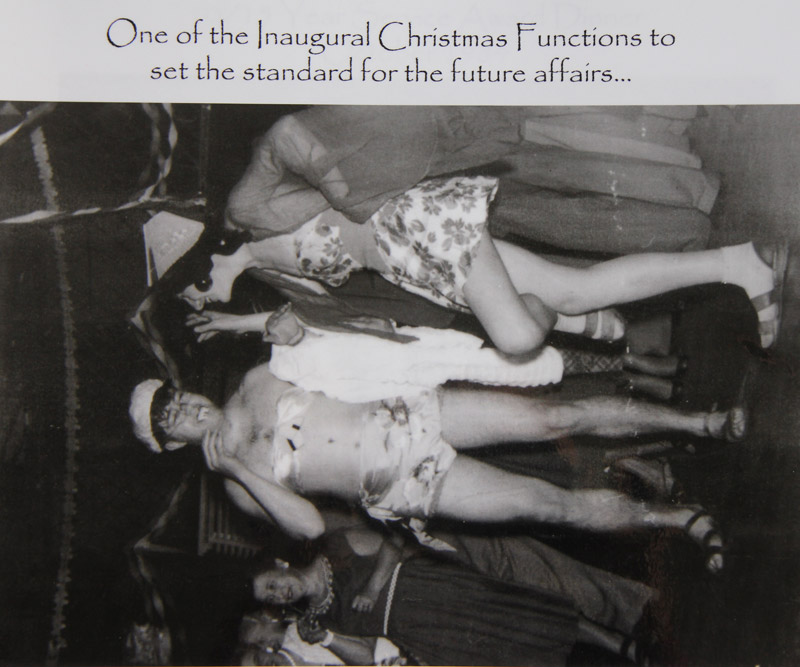

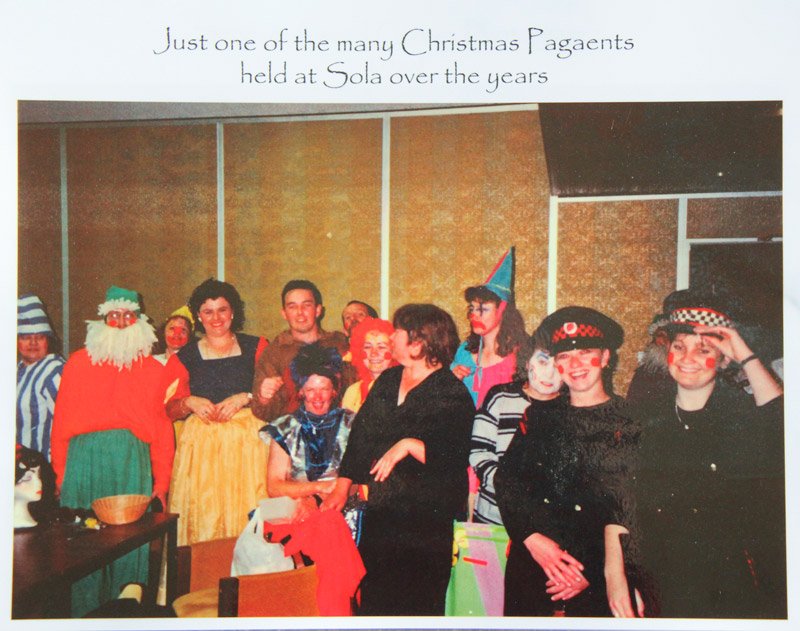

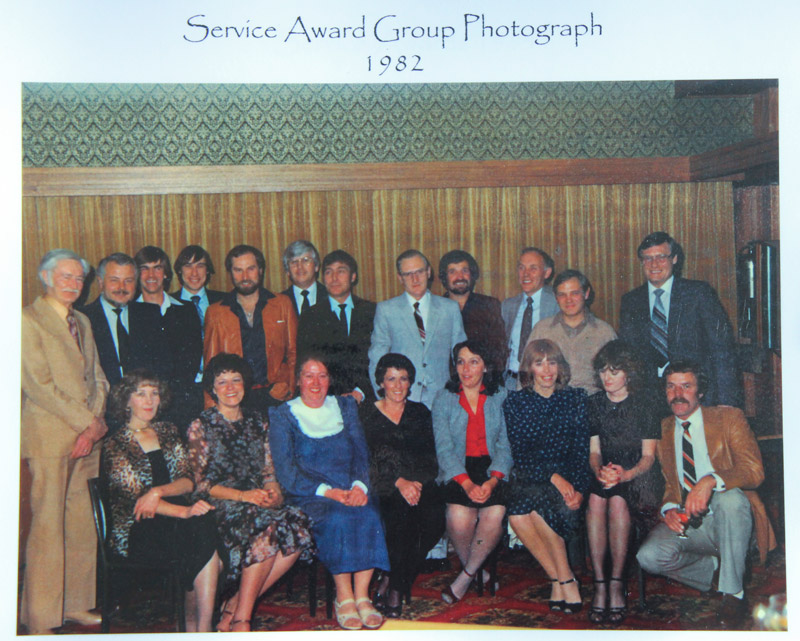

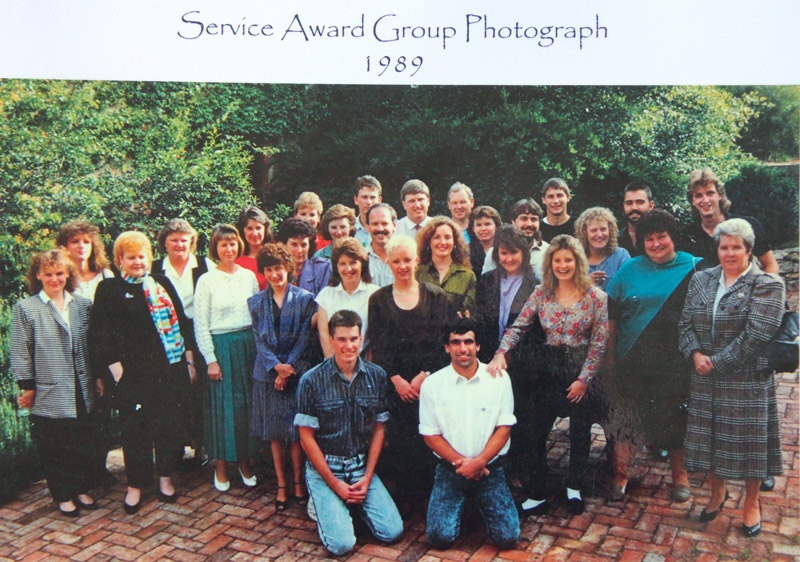

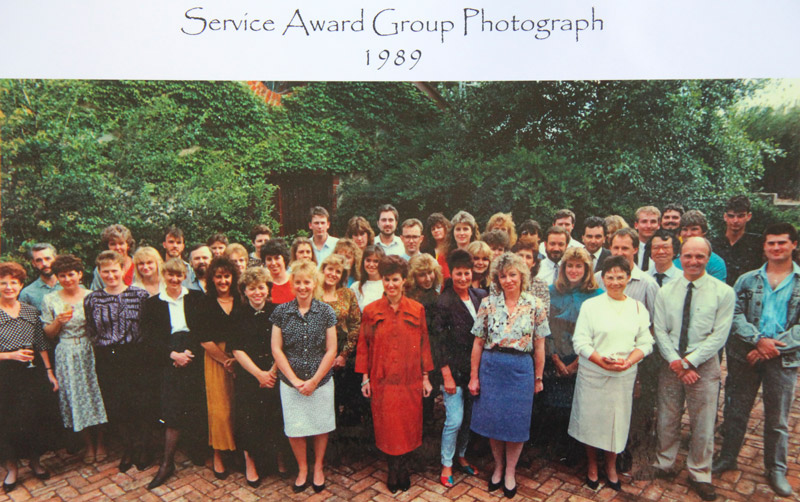

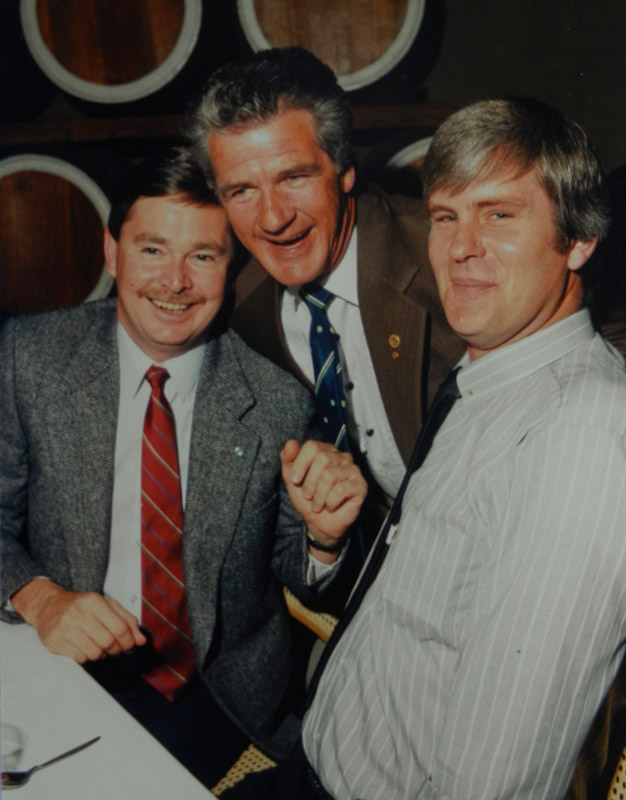

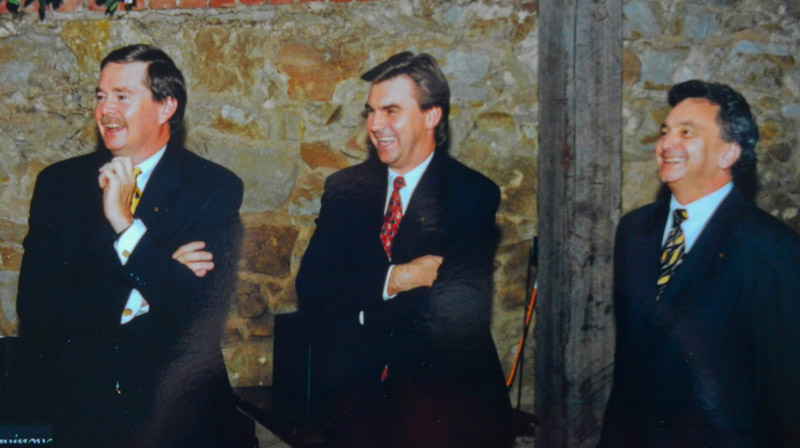

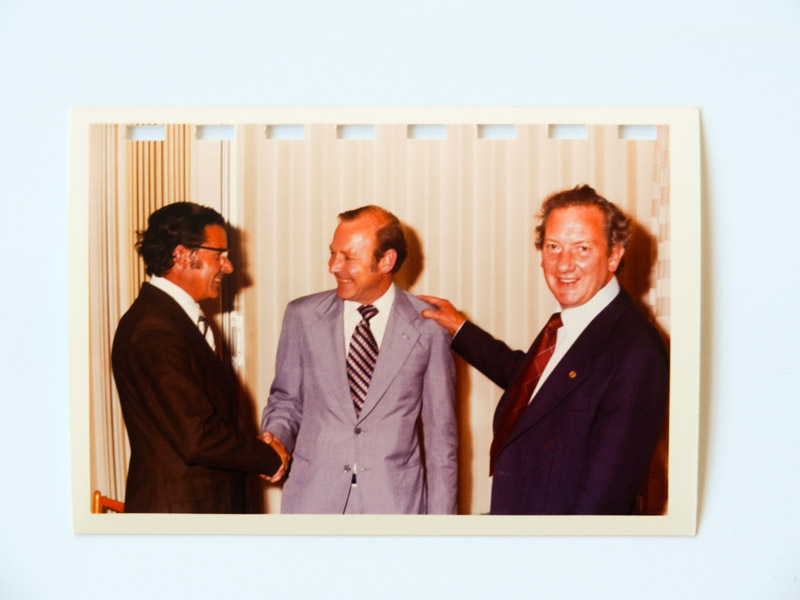

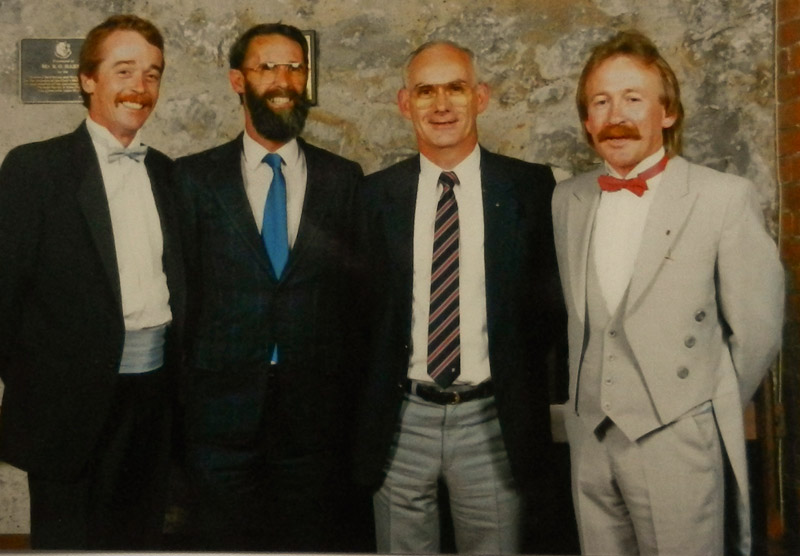

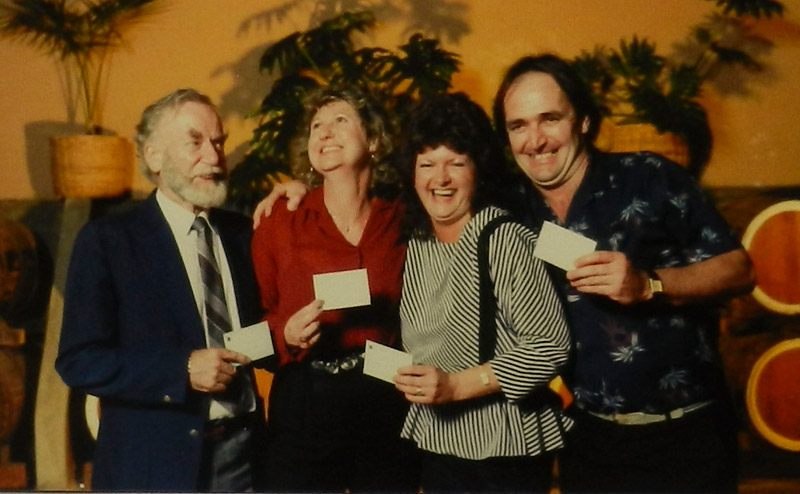

The culture in SOLA was arguably the key factor that contributed to its success. Even today get-together social events of former and current employees are common place.

| Click on images to enlarge: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Noel Roscrow commented in 2000:

...The team that was built up over the years was highly competent, loyal and capable of tasks that beset a company with an aggressive growth record.....

Rob Linn in one of his interviews for Breaking the Mold:

In SOLA, I still find it amazing that completely different cultures can actually sit down and work through issues and work across the board to create something better and not feel that their independence is being threatened at the same time. It's quite an unusual phenomenon.

An edited (to protect the writer) email from a “typical” SOLA Australia employee

“It is with mixed feelings I write to you and say farewell. Although I have been very upbeat about leaving/retiring there is a tinge of sadness about my departure when all is said and done.......

....25 years ago today (2009) I started as an on-call casual for the finished lens line. After my first day at work my husband asked me “how did it go?” I said “I hated it and didn’t want to go back”, however, that’s another story…

..... typical of SOLA, I was given many opportunities.....

.... my greatest respect and admiration will always be for the people on the shop floor without whom the business would never have flourished and succeeded as it did when our mainstay was manufacturing. Their willingness to put in when we asked them to, change their working hours, days and shifts and make alternative child care/family arrangements to meet the fluctuating needs of the business as production bounced up and down was testament to their trust and ownership in the company and was evident by the industrial harmony we always enjoyed. To them, many of whom are now gone, thank you.

I have been humbled and moved by others’ difficulties and adversities. I have had many lessons dished out to me by wiser people. One such example was when I was paged in the canteen by Lizzie one day many years ago. It had been a particularly busy and vexing day one of many at the time. I answered my page and was terse with Lizzie about being paged while at lunch. Lizzie’s response to me was “if it’s good enough for John Bastian - (MD at the time) to take a page anywhere anytime and answer it no matter how busy he is its good enough for you”. It got through to me in exactly the way Lizzie had intended, thanks Liz. Just one more SOLA life lesson.

There is no doubt that SOLA’s ethos and culture has shaped a large part of my life and afforded me the chance to undertake many opportunities, to work with many gifted and special people and learn many valuable lessons, for that I am very grateful.

The experiences have been too many and varied to list, some great, some good and some not so good. All of this has taught me a great deal about people, business and life and has certainly enhanced my personal and professional life.

To all my former bosses who all played no small role in shaping the business to meet the challenges at the time and made coming to work a sheer pleasure and from whom I learned so much, thanks.....”

Another edited (to protect the writer) contribution from 2001

To be honest, my departure from SOLA was painful but ironically it was the best thing that could have happened to me. SOLA was no longer the fun place where hard work got results. The company lost its sense of being and the bureaucratic style took over, where the sole purpose of senior executives was to boost personal ego and their sole vision was to make SOLA attractive to sell. Their vision horizon was for no longer than 5 years where the real SOLA guys always had a vision for life.

For what it is worth, I don't believe it is possible to put into meaningful words the success story of SOLA. It will never be a definitive business model for academics as it was more about the unlikely combination of Noel Roscrow and fellow executives accidentally capitalising on cultural differences by embracing them with the typical Aussie manner. Fortunately, for us here in ......., the Aussie culture was not too much of a shock, as it was similar in its openness and warmth but in other countries it was a lot more challenging. Nevertheless, SOLA had a remarkable effect of optimising the positive sides of cultural differences to the best effect. This is not to say there was not interesting clashes but in the end, it brought out the best in people. Articulating this to those who have not lived the experience is to my mind challenging, to say the least. However, if you find a way of putting this into words, then I'll look forward to reading the result.

Another contribution from Karen Roberts

In 1985 I joined SOLA Optical as a freshly graduated engineer, and at that time, SOLA Optical was on the cusp of becoming one of the major industry players as it expanded its manufacturing and distribution into global markets.

Part of this growth strategy was to invest heavily in Research and Development to support the rapidly growing demand for enhanced product portfolio and manufacturing capability. After reviewing a number of job opportunities I opted to take a process engineering position with SOLA on the basis it would be exciting to be part of this growth strategy for a couple of years. Little did I know I would be enticed by the remarkable fabric of SOLA, and stay on for a few more years, followed by another few, and another few, eventually clocking 26 years of service!

Through 1985 and the following decade, SOLA recruited some bright young scientists and engineers who complemented the existing experienced technical and operations team. From a new employee’s perspective the ‘experienced’ team presented a challenging and somewhat eccentric mixture of personalities to interface with and to learn from. A group of these characters seemed to have been part of SOLA since about the time they could walk, Phil Squires, Tony Guy, John Anderson, Hugh Tedmanson, Geoff Ward, Steve Willis, Bruce Neil, Bob Jose, Roger Goodale, Bob Young, Ray Seco, Helmut Halm, to name a few. They were the mainstay of the company’s manufacturing knowledge imbibed over years of innovative trial and error. This group was supplemented by another group of experienced veterans, Kevin O’Connor, Bob Sothman, Huan Toh, John McCarthy, Alan Vaughan, Tom Balch, Lino Barbieri and others who brought some additional qualifications and technical perspective to the mix. They were an integral part of a company culture that was lively, creative and unbound by conventional constraints. They fearlessly tackled new products, new ways of making lenses and went after every commercial opportunity with a confidence that if they weren’t able to service the opportunity now, they soon would be.

Over the years I had the pleasure of working with these folks individually and as part of a surprisingly functional group given the disparate personalities, learning both the craft of designing and fabricating lenses, and many additional life lessons to boot.

During my first 15 years at SOLA, John Heine was the CEO. John was a brilliant but intimidating character with a fierce competitive streak. His entrepreneurial nature complemented the foundation and culture established by SOLA’s founders and he went on to chart the business to a much expanded, thriving international business.

John’s primary objective was to ensure he had great people with strong characters and therefore strong convictions in every part of the company. He had the intellect and self confidence to allow him to incorporate input from these diverse and strong personalities, and a talent for driving consensus once the talking (and arguing) was done.

Subsequent CEO’s brought additional value to the company but none of them had this same confidence and capacity to tolerate, and more importantly, harness the diversity that SOLA represented.

This tolerance and respect for diverse thinking and input was a characteristic of SOLA that underpinned a unique culture of passion and intense loyalty to the company and to one’s colleagues. This stood SOLA in good stead over many years of growth and market challenge and I believe became the hallmark of many of the loyal long-termers who stayed because of that unique working environment.

At social gatherings where many of SOLA’s now elderly founders still get together, the loyalty and respect are still evident, and it is this enduring aspect that permeated SOLA’s culture that is still top-of-mind for many of the company’s former and current employees.

Over time it became necessary for a company that had expanded to a medium cap, internationally diverse organisation to implement some more rigorous procedures and centralised control to ensure synergies and best practice were being used to best advantage. This was a painful process for individuals and local business units used to a large degree of autonomy. This in conjunction with the challenge of becoming a public company listed on the New York Stock Exchange, with quarterly focus and accountability also compounded the upheavals SOLA went through in the late 90’s.

A contribution from Roly Lloyd detailing his adventurers and cultural experiences of being a SOLA employee working aboard

I worked in quite a number of sites - India, China, Kentucky and Singapore mainly.

India

Installation of the OLMIL project in Bangalore India - very interesting place to work – extreme wealth alongside extreme poverty... had to change your whole cultural thinking – when we were doing concreting there, as part of the factory set-up, the locals had whole gangs of women labourers carrying pots of concrete on their head .. so I wanted to get a cement mixer to hurry the job up and the local managers were absolutely aghast as it would have meant the “untouchables” would have no work and would literally starve - so rather than upset people I let them carry on with their little pots of concrete. Another thing is you had to be very mindful of the religious/cultural aspects in Indian. To many Indians, the cast system was more important than our traditional line management where a Braman was much more important than his supervisor who was not a Braman. An example was we had set a date for the launch of the casting line .... but for a couple of days before the launch date, although it was ready to go, there was definitely an unease around the factory amongst our Indian colleagues. Eventually we go to the bottom of the problem; the day we picked was not a propitious day. They would rather delay the launch to a more propitious day - the sort of cultural difference we would not normally have to deal with.

So we delayed the launch. However during the launch something quite funny happened. We had what we thought were fully installed smoke detectors and fire sprinklers throughout the line. Anyway during the ceremony it was decided to bless the line so they got these plates of oil and set them alight resulting in voluminous amounts of smoke right underneath the smoke detectors. We were all ready for the deluge but nothing happened and that is when we discovered they were not even connected. The project manager, Richard Stone, was absolutely aghast.

The cast system

It was quite hard to understand the pecking order. We had a tea boy whom all his colleagues used to treat really badly; we always felt sorry for him so we gave him cigarettes and such so he was quite happy with us. One weekend we had to do some work. When I went to the factory the guard house which normally had immaculately dressed guards but today everyone was in civilian or sleeping cloths or shorts. In the factory, the guy that was the tea boy who was given a hard time by everyone else was now in charge of the weekend cleaners and he was treating them terribly - and he was the very guy we felt sorry for.

The team that setup the factory was:-

Larry Whitke from America

Ken MacLeod

Karl Nolan

Hugh Tedmanson

Jamie McClelland

Roly Lloyd

As a factory set-up it was one of the best that SOLA ever did, even better than China. We hit all our targets and everything went to plan.

China

China was a fascinating place to work. One thing I learn in China was that jokes don’t translate very well. I did quite a bit of work setting up the second set of casting lines (SOLA BDP line). Subsequently I was asked to come back and implement a new warehouse layout and systems. So we had a meeting where I knew most of the people from my previous visit – so in a self-depreciating way I said, “I have come here again - you know me Allon and Johnson, etc – I have come here again to make a mess of things like I did last time ha,ha,ha. There was a little bit of a murmur in the room and then one young guy gingerly put his hand up and said “excuse me sir – why have you come all this way to make mistakes. So I decided jokes in China don’t go down so well.

I first started going to Guangzhou around 2000 or slightly earlier and the air pollution, traffic, etc was bad. It has now changed for the better. Years ago we never saw blue skies because of the air pollution; now you often see blue skies. It is a lot greener and a lot of the rubbish has been cleaned off the streets. It is so much easier to do business there now; when we first started going there it was an ordeal just to get a visa (letter of introduction, this and that document, etc) and it was difficult to get in and when you did get in you had 3 or 4 forms to fill in just to pass immigration. Now you can go to Hong Kong and get a multi entry visa same day over the counter. It has really been impressive what they have done there. It is also impressive what they have done with the SOLA/CZV factory in China. They seem to have a great work ethic and they latch onto what we teach them very quickly. I have always enjoyed working in China.

USA

In Kentucky - that was an experience in itself. I can remember the first week I was in Kentucky and the warehouse manager Mark Spiegel asked me what I was going to do on the weekend and I said I was going birding. Oh he said going birding. For the next few days there was quite an “atmosphere” between me and the ladies in the office – eventually Mark Spiegel said to me “I need to talk to you Roly – I don’t know what your customs are like in Australia but in America we don’t tell our colleagues, especially our woman colleagues, that we are looking for women on the weekend”. I said women, what you are talking about. He said “I understand ‘birds’ in Australia is slang for ‘girls or women’. Yes but I am going bird watching, which is ornithology – feathered birds flying around. The look of relief on his face and on the ladies faces was absolutely amazing. There was a cultural error in translation there.

Barry Dolan comments:

You tend to become very attached to the style of the company or the culture within the company. SOLA suited me anyway. My original intention was to stay in Wexford three or four years. Being from the city and that, I never really could see myself settling in a rural area like Wexford but I found this place kind of grew on me, if you like. Thirty years on, we've been very settled here, and I've no regrets.

Before joining SOLA, I worked for Johnson and Johnson, which was very different in style of operation. A very centralized control where all the senior managers were all the time in their pin-striped suits.

The first SOLA person I met was Noel Roscrow. He was dressed in jeans and a leather jacket and he had an open neck shirt, and he was very tanned, of course, being from Australia. A big medallion on. I can't remember the detail on the medallion but he looked extremely casual. And I remember thinking that this is a strange kind of setting for a job interview. But it was my first impression, if you like, of the Australian style, and I liked it. I must say I liked it. It was much more casual - seemed much more casual and laidback, but of course Noel is anything but casual.

And so, I had an interesting interview, and then we adjoined to the bar.

Mike McKeough’s first impressions when he joined SOLA in 1990

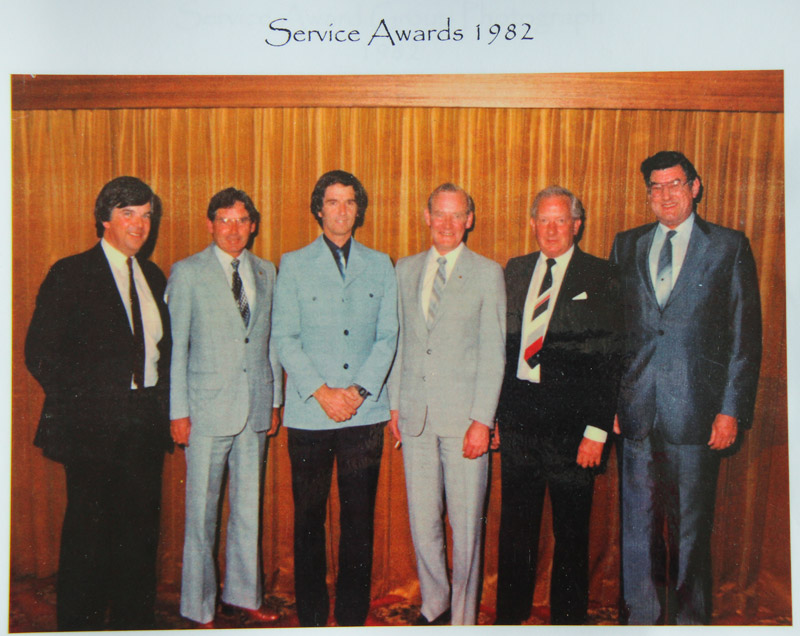

I was impressed enormously by SOLA. Jim Gall of the recruiting agency said that “SOLA worked hard and played hard”. For me that turned out to be true and was something I really enjoyed about the company. The 3 and 5 year service awards were fabulous shows and the 20 year awards were presented at a fabulous dinner. This culture of work hard and play hard was a really good environment. It undoubtedly started in Noel’s time and was definitely continued by John Heine. I never minded putting in the extra hours as I felt that there was sufficient recognition.

Having come from a Japanese company the degree of freedom I was given managing the mold group in SOLA Australia was refreshing.

As well, SOLA had a good way of bringing people into the organization starting with the interview process. Richard Altman certainly was instrumental in making this happen. As soon as I joined the company I was invited to morning teas of the management group under John Bastian - Mahoney, Altman, Willis, Zimmerman, Staples and Ward – quite a lot of friendliness that I had not experienced in my previous employments.

Within my first 12 months I would go to SOLA Group senior management meetings. The dynamic that really shocked me was the way Ray Seco and Bernie Friewald were at each other’s throat. It almost became physical. At the first senior management meeting chaired by John Heine, I turned up in a suit and tie as I did at my previous job and everyone else was in open neck shirts and slacks and very relaxed.

| Click on images to enlarge: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Effect of acquisitions

Over the years SOLA acquired many companies, some big such as the vision part of Revlon in 1988 and some small. In general they were assimilated into the SOLA Group mostly successfully and became part of, and contributed to, the great SOLA culture. Probably the key exception was AO. SOLA acquired AO for $100 million in 1996.

Dick Whitney quote:

Many AO employees were irritated by SOLA and the perception that they did not appreciate AO either.

Why was this?

AO had a much longer and more illustrious history than SOLA. Its history is captured in Dick Whitney’s website http://www.dickwhitney.net/RBWAOHistoryIndex.html. Additionally AO was acquired at a time just before an extremely low period in SOLA’s history and AO people played major roles in SOLA post-acquisition. Mo Cunniffe became Chairman, Jeremy Bishop became CEO.

Politics were seriously involved. A somewhat cynical view expressed to me by one senior SOLA executive:

In reality, SOLA did not take over AO. Rather SOLA USA took over AO. Given the 3-way company jealousies in train for years before, the attitude was aggressive and superior. Heine was about teaching AO how to be a “great company” again – thinking strategy when the cupboard was already almost bare. Mo had his own game in place and that was not about anything other than his wallet. He was far too cunning for little John E Heine.

There were heated discussions as to how to handle the new combined company and even what to call it. AO had a bigger presence in China where the name AO was well respected and associated with quality. It was also still “powerful” in the major market of the USA.

In North America SOLA became AO SOLA while in the rest of the world it was simply SOLA.

All this did not help the smooth integration of SOLA and AO.

SOLA International Graduate Program Jacqui Lang/Pugsley

The SOLA International Graduate Program was an initiative of John Heine. It was part of the program to better educate, attract and hold key SOLA staff. Duck School was another key initiative which is covered in Breaking the Mold (p. 233). Towards the latter part of John’s career with SOLA, he developed a passion for education. In Feb-1998, he was quoted, during a Robb Linn interview, as saying “We have a thing we call Duck School that is the most exciting thing I do in SOLA now. We've had three Duck Schools. We've appointed a Director of Education. We're going to have a Board of Education in the company. This is not training. This is philosophical education. And so, we've appointed a Director under Steve Lee. We're having two Duck Schools this year. We've done a tailor-made Duck School that we call China Duck, for China, which will happen later this month. We're having a senior executive Duck School. We've changed the sort of people that come to Duck School. It was sort of up and coming young people to start with. Now, it's anyone, irrespective of level, or age, in the company, who we believe has potential to learn. And we're going to start investing probably between half a million and a million (US) dollars this year (1998), and we're going to increase that investment as we've got the human resources to be able to manage it. See it as absolutely key”.

The SOLA International Graduate Program commenced in 1995 at Melbourne University. The aim of the program was to give university graduates training in a number of SOLA’s locations across a 2 year period. The program commenced with a Commerce stream and two years later an Engineering program began.

Both the Commerce and Engineering programs were excellent training grounds because graduates were exposed to many facets of the business during their rotations. Many graduates on the Commerce program spent some time working for Ted Gioia, Vice President of Strategic Planning in the USA. When working for Ted, tasks included putting together summaries of the competitions’ business and compiling data on the Optical Industry in various countries. Whilst on the graduate program, graduates would spend six to 12 months in one of SOLA’s offices or manufacturing facilities, before moving on to the next secondment. At the end of the program graduates were placed in a role that suited their strengths and interests.

The graduates on the Commerce program were:

- 1995: Jacqui Lang

- 1996: Dan Boulton, Frederick Wale

- 1997: Darren Crawford, Chi Lu, Daphne Yeo

- 1998: Ze-Min Chua,

- 1999: Meredith Chessell, David Potaznik

- 2000: Thomas Ko, Kerry Liu

- 2001: Benjamin Burt, Tenille McDonald

The graduates on the Engineering program were:

- 1997: Glen Taylor

- 1998: Emma Tickle

- 1999: Kara Anderson

- 2000: Lisa Caruso

In 2010 only one of the graduates remains with the company. Jacqui is a part-time Business Analyst, based in Lonsdale, for AURx and AU Supply Chain.

Key Characters at SOLA

The following summarizes the background and contributions of some of the early SOLA employees. Their backgrounds before they joined SOLA were quite diverse ranging from a 13 year old child straight from school (Graham Reed) to a political refugee (Leo Schleim who was arrested, on political grounds, during the Communist coup d'etat in Czechoslovakia but finally succeeded in fleeing the country in the latter part of 1948 and made it to Australia in 1949 as one of the first Czechoslovakian migrants).

It shows that a bunch of ordinary but very talented and motivated individuals can create a wonderfully successful company.

Roger Goodale

SOLA employee from 1953 (Laubman & Pank) to 1993

Key positions held: R&D Manager, Director of SOLA Optical

Roger was also one of the original 9 SOLA employees.

He started at Laubman & Pank in 1953 aged sixteen, i.e. straight from school. He was initially employed as a hearing aid technician.

Roger’s early education was in the electrical and radio trades. He then completed, part-time over a 10 year period, a Bachelor of Technology in electronic engineering as well as a course in plastics molding and technology.

In Laubman & Pank he worked on instrumentation, such as photographic electronic flash units, light meters, and then on coating lenses after a high vacuum coating unit was purchased.

About that time, Ron Ewer started doing experimental lenses casting with CR-39 and Roger was seconded to help, so was involved from the outset.

The initial castings were with a readily available catalyst, benzoyl peroxide but the lenses were yellow. So the development of a better catalyst, IPP, was paramount. IPP was finally synthesised with the help of Harold Rodda from the Organic Chemistry department of The University of Adelaide. Tom Kuruesev from the Physical and Inorganic Chemistry department contributed significantly in improving the casting performance. Ron Ewer and Roger spent time with both Harold and Tom.

The synthesis of IPP was improved to the point where it was usable as a catalyst for CR-39. Initially there were stability problems as it was just stored in a refrigerator rather than in appropriate colder storage; consequently the mass of material that was there was enough to ‘thermally take-off’ and blew the door off the refrigerator. Subsequently the correct storage temperatures were implemented and no further major storage problems resulted. Refer section 4.3 SIP – A Quiet Achiever without a Big Bang (pun intended) for more detail on the explosive properties of IPP.

Roger recalls,

It was exciting times as casting CR-39 was very

new and a whole new territory for everybody

From 1968 to 1975, Roger was a Research and Development engineer, then R&D Manager and, in his later years at SOLA, Technical Development Manager involved in overseas support and start-ups overseas.

Graham Reed

SOLA employee from May 1957 to July 2003

Key positions held: Mold maker, Manager SOLA Singapore mold making factory 1975 until December 1978, then Assistant Manager of Mold Manufacturing Australia

In 1957, Graham was a thirteen year old schoolboy whose father was fairly seriously ill so it was decided that he needed to earn a quid and help support the family. On this particular day, he and his mother were walking the streets of Adelaide trying to find a job and, as luck would have it, his Mum wore a hearing aid which she’d bought from Laubman & Pank. So they walked into Laubman & Pank to buy a battery for the hearing aid and got talking to the woman that ran the hearing aid centre (it was a lady by the name of Eileen Rogers—a lovely lady) and it came out that Graham was looking for a job. So she excused herself for a few moments, disappeared, and came back and said, ‘Come and talk to these people’. So Graham was introduced to Don Schulz and probably David Pank - and within the space of about ten minutes he was employed by Laubman & Pank.

His first job was in the Rx jobbing shop, i.e. the prescription lens jobbing shop.

Eventually he was given an apprenticeship as an optical mechanic with Laubman & Pank and finished it with SOLA once SOLA hived off from Laubman & Pank and relocated to Black Forest.

The Rx jobbing shop at Black Forrest helped support the business during the development of CR-39 as the workshop was doing all the jobbing work for Laubman & Pank. However it then started to make molds for the CR-39 casting. At that time, making molds, in terms of grinding and polishing glass, was very similar to Rx. A mold was just a bit more complex and has tighter tolerances. At that time the casting operation—SOLA’s business—was starting to grow rapidly and so did mold making. SOLA was moving forward very, very quickly.

A key player was Doug Riley; he picked up the responsibility of making the special, more difficult molds. He was doing that pretty much solo at the time, so Graham got enlisted to work with Doug and help him make those particular types of molds. Initially there was just Doug and Graham. However Doug then had other responsibilities which were to travel around the world and sell and set-up Rx workshops as turn-key packets. The equipment included Coburn, or Schulz machinery as it was known in those days. Ross Schulz’s company was making the optical equipment. SOLA would supply the lenses, or the semi-finished blanks, and the technology, resulting in a turn-key operation. The whole thing’d come in. Doug would install the equipment, train the operators. So that took Doug away from mold making and Graham was left on his own.

It was Don Sara, Production manager, that came one day and threw Graham a key to the front door. He said ‘you can work as much as you like and as long as you like’. So there for a while it was pretty much get to work when he wanted to and work right into the night. You couldn’t do it today.

He’d work up to ten or eleven o’clock at night including Saturdays and Sundays. When absolutely knackered he’d go home after locking the door.

Then Graham had a knee operation as a result of some football problems, and was home, propped up on crutches when Don Sara sent Doug Riley around to see Graham said, ‘You’ve got to come back to work. We’re going to develop this new flat top mold’. It was about this time they wanted to develop a flat-top lens that SOLA could sell. So Doug and Graham worked developing a flat top mold’, with Graham hobbling around on crutches behind Doug. They finally nailed it. And about that time Noel came back from one of his overseas trips, and just simply said, “Oh, I’ve just sold so many thousand flat-top lenses”. Graham said, “Hang on! We don’t have the mold fully developed yet. We’re just learning how to make it”. So that put a bit of pressure on the system but in the end the molds were made.

At the time of the move from Black Forest to Lonsdale, there were three, very separate mold making departments. First was planos with Fred Brookner and then Jim Mott in charge. The second was stock lens with Brian Hill in charge and the third was special molds with Graham Reed in charge.

A key quote by Graham Reed in September 1999, from Breaking the Mould

SOLA to the Core – you know I have been around the world a few times. Travelled here and there. I would probably never have had those opportunities without SOLA. I started at 13, I am 55 now. I think you could cut me as deep as you could cut me and you would see SOLA stamped right through there. Everything I own and everything I’ve experienced has all been SOLA

Doug Riley Dennis Jarvis

SOLA employee from 1935 (Laubman & Pank) to 1978

Key position held: Mold maker

It was by chance that Doug Riley became involved with Optics. Back in 1935 Doug had just finished school and was helping his father, a carpenter, do some alterations at Laubman and Pank at Gawler Place, Adelaide. While helping his father he was approached by David Pank’s father to start an apprentice in surfacing and Doug accepted the offer. At that time prior to the introduction of processing equipment using impregnated diamond wheels, the basic medium for grinding glass lenses was different grades of abrasives all carried out on machine similar to a potter’s wheel. This was method used some years later in developing the early molds for casting CR-39 semifinished blanks.

Doug came into mold making by tragic circumstances as Arch Patterson had been designated as the person to develop the glass molds for casting CR-39. Arch passed away unexpectedly leaving Doug to take over the mold development role as well as training others in the process. Following the making of round segment molds, he began to experiment with flat top molds; this required the fusing of two pieces of glass, a skill that had been learnt in wartime when glass bifocals were unavailable.

After SOLA was incorporated in 1960, Doug left behind the Prescription Lab to concentrate on making molds and training mold makers. New techniques were developed to take out some of the extensive labour time. At the time, American Optical was the only company to have a CR-39 Executive (E-line) bifocal, and so Doug became involved in making the molds for a SOLA product and in the process improved the existing AO design, which was not decentred for right and left. This product became very popular, especially in North America.

Sometime later Doug was asked by Noel Roscrow to develop a trifocal based on the previous E-line design, which was called an ED trifocal, a design that was unique to SOLA. From those early days Doug would always wear his ED trifocals.

Ron Ewer wrote in the November 1978 SOLA newsletter ....

After 44 years of service with Laubman & Pank and SOLA, Doug Riley has decided to fold up his lens working equipment and spend a few years outdoors in the Riverland on a fruit block.

SAD DAY

It is certainly a sad day for SOLA to lose a man of his capability. Doug commenced with Laubman & Pank on 4th February 1935 and during his 27 years of service with that company, spent a good deal of time perfecting surfacing techniques. He was, in fact, much involved in the design and development of the first glass generator built and used in Australia.GENERAL TECHNICAL ABILITY

Upon the transfer of SOLA to the new location at Black Forest, Doug took over the supervision of the glass workshop and with his great technical ability he has played a major part in the development of the CR-39 surfacing systems. CR-39 processing was unknown in Australia at that time and very little work was being done worldwide. During the following years he travelled overseas on several occasions to setup workshops and troubleshoot where appropriate. He also spent a good deal of time studying new equipment and, after a visit to LOH machinery manufacturing company in Germany, was responsible for the decision to buy the equipment that is now working extremely well in the Lonsdale plant.Over recent years, bifocals and specialised mold-making has been the greatest contribution from Doug. His influence on the design and manufacture of E-line and flat-top bifocal molds, ED trifocals and the new Hi-Drop has been of major importance.

Since 1962, Doug has led our fire squad from a relatively small group to an efficient organisation necessary to maintain safety in our present large plant and he has also been a member of the safety committee.

DEDICATION

We are not quite sure of the first 24 years of Doug’s service but over the last 20 years, he has only had approximately 20 days sick leave, and indication of the dedication of this man.SOLA has been able to achieve its present position in the world CR-39 scene only by the efforts of of such people as Doug Riley. Clearly Doug has made a wonderful contribution and we certainly wish him every success in his new venture and sincerely hope that he has the time to further assist SOLA in the future.

David L Pank also wrote in the November 1978 SOLA newsletter....

I am often asked the question: How is it that SOLA is able to compete on International Markets with countries like Japan and USA.

There are a number of contributing factors in the SOLA success story. I believe the principal factor could well be the painstaking dedication, persistence and pride in workmanship displayed over many years by our migrant and Australian-born tradesmen – of which Doug Riley is an outstanding example.

Doug and I are contemporaries in that we commenced working for Laubman and Pank within a few months of each other – and Doug never lets me forget I am his junior!

WORKED TOGETHER

We served our apprenticeship and worked together for many years. Doug may well have decided to become an Optometrist but elected to apply his skills to the practical aspects of laboratory work – and it is very fortunate for the organization that he did.END OF AN ERA

Doug’s retirement marks the end of an era for L&P/SOLA. It is wonderful to know that Doug is young enough and fit enough to be able to devote a number of years to something that has obviously been close to his heart for a long time.Doug has been generous in his willingness to pass on his knowledge and skill to others, so we are happy that, in this way, the influence of Doug Riley will remain at SOLA for a very long time

Doug and Ruth – our very best wishes – and we expect to see you both at 25-year club functions for many years.

Dennis Jarvis

SOLA employee from December 1960 until March 31, 1990

Key position held: Manager Marketing and Sales AU & NZ

Before he joined SOLA, Dennis was an optical mechanic for OPSM running their Victorian laboratory in Melbourne. He was very happy with his job with OPSM but saw in the Melbourne Age newspaper an advertisement for a position with Laubman & Pank-cum-SOLA in Adelaide. And it related to plastic lenses. Dennis, like most others at the time, never knew plastic lenses existed. Everything was glass. So he applied for the position and within a little time received a letter to come to Adelaide for an interview with Noel Roscrow. Dennis saw the potential for plastic lenses - right from that day. But everybody within the industry in Melbourne said, 'Oh, plastic lenses, they will never ever succeed'. But Dennis was like Noel, he believed they had a tremendous potential. So that was the motivation for him to join SOLA. It was rather a brave move to bring his wife and young family to Adelaide and set up there where they knew nobody, and in point of fact, received less pay than he was receiving at OPSM, Melbourne. But he just believed in the potential ...... and ended up making a significant contribution to SOLA over many years.

Phil Squires

SOLA employee from 1956 to 1994

Key positions held: optical mechanic, R&D researcher (also state cricket player!)

Phil was born at Uraidla on June 18 1939, although he can’t remember the exact time of day. He lived at Summertown, in the Adelaide Hills for 32 years.

He commenced work at Laubman & Pank on 16th January 1956 as an apprentice optical mechanic. When SOLA expanded from Gawler Place to Black Forest to Lonsdale, his young family moved to Reynella in 1970 so as he could be closer to work at Lonsdale.

Phil was also one of the original 9 SOLA employees.

When the first 9 people were being selected, Noel Roscrow brought Phil into his office and said, 'Look, we can't pay you as much as you're getting at Laubman & Pank, but I'll guarantee you that you'll get overseas trips, the company will expand - worldwide'. That's how much faith Noel had in SOLA. And 13 overseas trips later and 14 manufacturing sites overseas for Phil, he was true to his word.

Phil ended up in R&D as Don Schultz taught Phil how to do the calculations to determine the front and back mold curves that, after the CR-39 monomer shrunk during curing and the molds bent, and twisted, and contorted, would give the correct optical power of the CR-39 lens. All this was before computers or even calculators so seven figure logarithmic calculations were used.

Key people Phil worked with in the early days were Cliff McPhee, Arch Patterson, Bob Wake and Max Hamill.

Phil described the atmosphere at SOLA at that time as ‘magic - like a real close knit family’.

Phil went on play a key role in many of the CR-39 casting developments.

Leo Schleim

SOLA employee from 1966 (as a consultant) to 1985

Key positions held: salesmen, translator, air travel and freight negotiator

Leo was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia. After the Communist coup d'etat in Czechoslovakia, he was arrested, on political grounds, but finally succeeded in fleeing the country in the latter part of 1948. He came to Australia in 1949 as one of the first Czechoslovakian migrants to Australia.

When he arrived in Australia he spoke the Slavic languages, Czech, Slovakian, Polish & Ukraine as well as German, English and some Dutch. When in Australia he studied Spanish and Portuguese. As most of the other migrants had done, he signed a two year working contract with the Australian Government and on arrival in one of the International Refugee Organisation ships, finally landed in Melbourne and was transported to Bonegilla, between Albury and Wodonga.

Initially he organised concerts for migrants in various parts of the outback in Australia, mainly due to the fact that in those days there was a large percentage of resentment against the newcomers, and it was the Government's wish to show the culture and art and music and all that the migrants were bringing with them. He left the camp in September 1950 and went to Sydney where he got a job still under the two years contract, first with Namco, the furniture people, and then with Prouds the jeweller where he finished his contract in 1952.

In 1966, having read about the first successes of the lens manufacturer SOLA, he one day went to see the Managing Director, Mr Noel Roscrow, and offered his services as a consultant and commission salesman with the aim of opening markets for SOLA where SOLA either had never been or had no contacts, e.g. Central and South America.

After a few discussions his proposition was accepted and thus he organised what he called “one man trade missions” to South and Central America. When he came back he presented reports to SOLA management, with the comment that there was a world-wide resentment against plastic because of very bad quality & incredibly poor scratch resistance. So it was a fairly hard job to convince the world about the changes in the quality and the advantages of the new CR-39 material. However, the more he got involved with SOLA, the more he got interested in the development of CR-39.

Through his input, SOLA was able to open up the market in Central and South America. Orders would come to Adelaide and the lenses exported from there mostly by air directly to the various destinations in South America. Initial orders were for plano sunglass lenses. As the orders increased, it didn't take very long before SOLA management realised the potential that existed in these areas. The idea of starting a manufacturing plant somewhere in South America took shape. Refer section 4.3 Brasil -The Early Days (1970 to 1998) by Bob Jose for details on the start-up of the Brazilian factory.

Leo was of the opinion that, compared to many other Australian manufacturers in those days, SOLA was genuinely export minded despite the fact that no one in the management could speak any language other than English. According to Leo, Noel Roscrow’s vision and PR work in English were absolutely second to none.

As time went on, Leo was used more and more as a translator and would travel overseas with Noel Roscrow to many countries, especially in Europe and Central and South America where he would find out what the markets, various customers, accounts, etc were like and then to get the real atmosphere within that particular organisation.

Undoubtedly Leo made a major contribution to SOLA’s overseas expansion.

His other main role was to negotiate all SOLA’s flight and export air freight bookings. At one point, 80% of lenses manufactured in Adelaide by SOLA were exported, mostly by air. He had the leading Australian airline at the time, TAA absolutely eating out of his hands by giving them all SOLA’s freight from Adelaide to Sydney and in return SOLA received free or upgraded flights around Australia. He also struck bargains with many different airlines e.g. Japan Airlines who delivered goods for SOLA to UK for $1.10/kg when the common rate was around $3.00/kg, having found out that Japan Airlines flights were heavily loaded from Europe but not the other way. Thus SOLA sent tons of plano lenses that way. Similarly, he organized similar deals to USA, Asia and South America with various airlines with the result that there were many free inaugural flights and constant upgrades.

Bob Jose

SOLA employee from 1970 to 1985 (although he was a consultant from 1957 to 1970 and from 1985 to 1994/5)

Key position held: Deputy Managing Director

After service in the RAAF, Bob Jose graduated in Mechanical Engineering in 1959. After 2 years factory experience, he joined PA Management Consultants as a trainee in the UK. He became a consultant when he moved to Australia in 1953. In 1957, David Pank employed him as a PA consultant to do work study in Laubman & Pank’s optical workshop managed by Arch Patterson and Douglas Riley. David picked a bright spark called Noel Roscrow to work with Bob. After that assignment, Bob went to Perth for a couple of years.

After his return, David Pank arranged with PA for him to attend meetings of the board of the group operating company Optics Australia Pty Ltd, the members being David Pank, Don Schutz, Frank Bawden and Noel Roscrow.

In 1959 Noel persuaded David Pank to buy a premise on South Road, Black Forest and SOLA was split from L&P. Most of the hard research, product and process testing and plant design and manufacture occurred in the decade to 1970. During that decade, Bob visited SOLA quite frequently when PA worked with Dean Sherry on the direct costing and accounting project. Refer Section 10, Recollections of Former Employees, As I saw SOLA 1958 – 1987, Dean Sherry.

Bob joined SOLA in 1970 and after a short time Noel started to take him to meet major clients in Sydney. Bob recalls “How to fit twice as much into one days work”

After transition to Lonsdale, Noel continued spinning around the world, especially in USA, and it was clear that he needed Bob to look after correspondence, enquiries, etc from worldwide customers and potential opportunities. When Noel was home, Bob tended to visit growing Asian customers, supporting Benny Sato in Japan, and introducing Samson Li to sales in Taiwan, Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia. The Hong Kong office which was opened mainly for financial reasons became the hub of all sales outside Japan

From the beginning of manufacture in Brasil and the departure of MacGuinness, Bob was given responsibility for the operations - initially he spent 3 months there and appointed Aurelio Seco as Regional Director. Bob’s basic responsibility was to connect SOLA Brasil to head office, which involved close relations with Seco and regular quarterly visits to oversee all operations. In 1985 Bob left SOLA but continued as a part-time consultant until 1994/5 reporting to Ian Craig and then John Wilen and then John Heine on South America. Further details are in section 4.3 Global Manufacturing – Brasil - The Early Days (1970 – 1988).

Dr Franco Gaslini

SOLA employee from 1974 to 1999

Key position held: Director and General Manager of SOLMA, the joint venture between SOLA & Mazzucchelli in Italy.

Franco made a major contribution to the SOLA operations in Europe, especially SOLMA. He was well like by all who worked with him and was a true gentlemen .... one of the true SOLA characters. His nick name was “the Duke”.

He was born in Milan but his family moved to Varese when he was one year old. He attended school in Varese and then in 1945 went to the University of Milan where he graduated in chemistry five years later. His first job was in a research laboratory where he was involved in fundamental research in wood chemistry and became, incidentally, one of the very few Italian chemists who published a paper in the journal of the American Chemical Society.

In 1967 he joined Mazzucchelli as Production Manager of the finished product division, with a staff of about 800. Then after a couple of years Mazzucchelli developed a divisional structure and he became the manager of the Finished Products division (production, sales, etc).

Mazzucchelli was then:

- world leader for plastic sheets to produce spectacle frames

- had a very high production level (one million of dozen of sun-glasses per year)

- produced 75% of the Italian toothbrushes, skis, combs and many other similar products.

At that time, the fashion, at least in Italy, was diversification. Mazzucchelli was looking for something new to do. They became interested in CR-39 lenses which were starting to appear in some sun-glasses. So they started to look for a possible partner or a company giving them the know-how.

Finally after a couple of years, a Mazzucchelli man finally succeeded in convincing Noel Roscrow and Bob Jose to come to Italy to talk with the Mazzucchelli family. Noel and Bob were able to make a sufficient impression that a partnership was put together between SOLA and Mazzucchelli. It was not an easy partnership as the people involved were completely different. On the one side, there was the Mazzucchelli family - really having a lot of money and present as entrepreneurs in the Varese area for five generations. Franco Mazzucchelli (President of the Company) went hunting tigers in Siberia. He had a wonderful yacht. He went sailing in the most famous Mediterranean Sea. He drove his Ferrari every morning.

On the other side there was Noel Roscrow and Bob Jose, taking care of every cent, because, at that time the SOLA Australia policy that David Pank established was that 50% of the profit of the company was to be distributed to the shareholders and 50% for the growth of the company and being a very, very fast growing company, they were absolutely always short of money.

But anyway, mainly due to the pleasant impression Mazzucchelli had of Noel Roscrow, Noel became very good friend of Franco Mazzucchelli; the partnership flourished.

Franco was able to make SOLMA a successful and profitable part of SOLA. It was Franco who pushed going to retail in Europe, i.e. to convert the business from wholesale only to one also focussed on direct to retail. Thus a key achievement was the setting up of a SOLA Rx lab near Varese that supplied much of Italy. Clearly Franco was well ahead of his time as it was many years later that Essilor commenced buying Rx laboratories around the world and even later the rest of SOLA realised the logic of Franco’s & Essilor's strategy and commenced buying Rx laboratories. Refer Section 3 Rx – delay in SOLA responding to the trend of vertical integration (1990s) and section 4.4 Rx for more detail.

Lino Barberi makes the following comments on Franco:

A contrast of a sophisticated, multicultural person and a simple, humble man – he used to walk at least twice a day along the casting lines and the prescription lab, talking with people on the shop floor. He always was aware of his workers family situation, asking questions regarding health conditions of kids, husbands, wives …

Pretending a lot from his co-operators but always helping them in achieving the assigned missions.

Going out of the factory, even at late hours, his office window was always lightened and his door opened … just for 10 minute discussion or even for 1 hour, if somebody had a problem.Sophisticated in his personal tastes and intolerant towards arrogance of somebody who pretended to ‘know everything’. Fantastic capacity of getting to the point of essential reasons of a problem.

His sense of humour was outstanding. Celebrating the 25 years of SOLA Italy, during his speech the maintenance workers made a hole in a partition of the main entrance and inserted a support for a bust that was commissioned by a sculptor, based on some pictures of him. The result was surprisingly realistic. When he was invited to the ground floor to have a photo with the group of old SOLA workers, he saw the bust and he was standing for some seconds without commenting.

Franco was not used to sentimentalism; his only worlds were “do you mind if I stick a post-it advising that the living model is at the second floor?” (Italian tradition is different to the British, the bust is only for somebody who passed away … but we counted on his understanding).

A little imperceptible tear of gratitude was on his eyes.

Further information on SOLMA is in section 4.5 Sun Lens Italy and Section 4.7 Europe and American Sales & Marketing. A photo of Franco is in section 4.4 Recollections of SOLA’s History in Rx Laboratories.

David L Pank AM AFC 1917–2004 Rod Watkins

Optometrist, and business and community leader

David Pank was by far the most successful person to combine clinical optometry and business management at any time in Australia and perhaps in the world. He was a practising optometrist for much of his working life. He chaired the board of directors of Laubman and Pank, Australia’s largest group optometry practice, from 1948 until 1994, during which time the practice opened branches and consulting rooms in 250 towns and cities around Australia. He was also chairman of the board of directors of the global ophthalmic manufacturing company SOLA Holdings Ltd from its inception in 1960 until 1988, when the company had manufacturing operations in 11 countries and employed 6,000 people. He chaired the boards of major national and international management organisations and of many government bodies and community groups. Despite his involvement in planning and managing large-scale operations, David Pank was always concerned for the well-being of the people within his organisations, providing them with guidance and opportunity to achieve their goals. His family and friends were of central importance throughout his life.

Laubman and Pank

David Pank’s grandfather, George Pank, was city building surveyor to the City of Adelaide. His father, Harold Pank, was one of seven children, all of whom were accomplished musicians. Harold became an optometrist and on a musical visit to Broken Hill, called on the local optometrist, Carl Laubman. The two became friends and Pank convinced Laubman to move to Adelaide in 1908 and join him in a partnership.

Laubman and Pank were committed to the highest standards of clinical practice, to technical innovation and to good management principles. Laubman and Pank travelled to Europe and the United States of America to study the latest practices in optometry and lens making. They invented and patented several items of ophthalmic equipment and introduced new products and manufacturing techniques to their practice. They had a keen scientific curiosity and an interest in music and the arts. Harold Pank and his wife Joanna had four children of whom the third, David, was born in 1917. His mother, who was a nurse at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and later a chiropractor, died when David was 13. David followed his father and was indentured as an optical mechanic at Laubman and Pank in 1934. Unfortunately, his father died the following year but the Laubman and Pank environment of enthusiasm and the pursuit of high standards of achievement, as well as mentoring by Carl Laubman, had a strong influence on David.

Optometry

South Australia had enacted an Optometrists Act in 1920, the third Australian state to do so. To become registered as an optometrist, it was necessary to pass the Optometry Board examinations. At that time, all apprentices at Laubman and Pank started as optical technicians and it was a matter for individuals to show initiative and to obtain enough training and experience in optometry to sit the examinations.

An optometry course had been established at the University of Adelaide in 1925 and David Pank enrolled in this course in 1938. The principal lecturer in the course was Don Schultz, the nephew of Carl Laubman and a fellow Laubman and Pank employee.

The Second World War interrupted Pank’s training, when he joined the Royal Australian Air Force. He became a squadron leader and an experienced flying instructor and was awarded the Air Force Cross. This gave him a love of aircraft and flying that lasted throughout his life, and a firm belief in the importance of disciplined training.

At the end of the war in 1945, he completed the optometry course. After qualifying, his work at Laubman and Pank continued to combine bench opticianry with clinical optometry but his management role quickly developed. In 1947, with Don Schultz he acquired a controlling interest in Laubman and Pank Pty Ltd and was appointed a director of the company. He continued the commitment to innovation, with an emphasis on good management and training. As far as possible, the practice was structured to provide optometrists with autonomy, responsibility and the freedom to pursue personal interests. David Pank quickly expanded the activities of Laubman and Pank into areas other than clinical optometry. Shortly after the war, he established the optical wholesale company Jemma Optical Pty Ltd in partnership with Gibb and Beeman in Sydney. Laubman and Pank acquired the largest manufacturer of bifocal blanks in Australia, Bylite Pty Ltd, and invested in the frame and sunglass manufacturer, Distinctive Products Pty Ltd. In 1964, it incorporated Laubman and Pank Audio Visual Aids Pty Ltd for the prescription and sale of hearing aids and in 1965, incorporated Soltec Pty Ltd to sell telescopes and photographic and electronic equipment. During this time, David Pank was both a practising optometrist and active in the political affairs of the profession. He was a member of the state and national councils of the Australian Optometrical Association for many years and state president in 1958. In addition, he was a member of the 1953 National Campaign Committee that responded to the proposal to exclude optometry from a national health scheme and again in 1966, an adviser to the association in its planning for inclusion.

SOLA

David Pank provided great support for the technical innovation of his partner Don Schultz. Schultz had worked on optical systems at the Weapons Research Establishment in Adelaide during the war and several projects were continued within Laubman and Pank. An instrument construction department was set up to repair binoculars and to make a range of ophthalmic and defence instruments. In the mid-1950s, Schultz began to take an interest in the new optical polymer called CR-39. Some lenses were cast and market evaluation was carried out in Europe. As a result, a new company called Scientific Laboratories of Australia Pty Ltd (later SOLA International Pty Ltd) was established in 1960 to develop the material. This decision was controversial within Laubman and Pank, as SOLA took all available cash from the optometric practice and required considerable additional financial commitment by many of its members. It was only through David Pank’s leadership and strong support for SOLA that this was possible.

As well as chairing the board of directors of SOLA, David Pank was actively involved in large-scale corporate planning issues, such as the establishment of manufacturing subsidiaries in Japan in 1968, the USA in 1971, Hong Kong and Italy in 1972, the UK in 1973, Brazil and Singapore in 1975 and Ireland in 1978. The company doubled in size every two years during the period of his chairmanship. Fortunately, he had developed an interest in formal management systems and this rapid growth was facilitated by his knowledge of management procedures that were always in advance of those needed at any time.

While conceiving and implementing global plans, he still found time to be personally involved with people in the company, particularly with their career planning and training. The Laubman and Pank group of companies was separated from the SOLA group in 1970 under two holding companies. David Pank chaired the boards of both. He retired as chairman of SOLA Holdings Ltd in 1988 and as chairman of Laubman and Pank Holdings Pty Ltd in 1994. In 1981, the Pank family established and funded the Pank Ophthalmic Trust, an independently managed organisation that supported people in the ophthalmic industry, in optometry and in vision research, who had ideas that needed seed funding. David was particularly interested in helping people within the industry to achieve their goals. In 2002, the family established the Pank Prize for Entrepreneurial Activity at the University of South Australia to help young people to establish their own businesses.

Throughout his life, David Pank encouraged the promotion of formal management principles and was involved in national and international management organisations. He was national president of the Australian Institute of Management from 1974 to 1976, and was awarded its John Storey Medal for distinguished contribution to management thinking in 1981. He was president of the Asian Association of Management Organisations from 1977 to 1980 and vice-president of the World Council of Management, also from 1977 to 1980. During his life, David Pank was a member of the boards of many companies and organisations unrelated to Laubman and Pank or SOLA. He chaired the boards of a life assurance company, a winery, a building company and a scientific equipment company. David gave his time and management skills to many community-based organisations but particularly those concerned with education and training. He was chairman of the University of Adelaide research commercialisation company, chairman of the state government’s technology parks initiative to link industry and universities, and founding President of the South Australian College of Advanced Education. He was a member of the council that established the University of South Australia in 1991. He chaired the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, a leadership program for young people, and he chaired Bedford Industries, an organisation that provides training and employment for people with disabilities. He chaired fund-raising committees for the Royal Adelaide Hospital, the University of Adelaide medical school and for vision research in Australia. He was a council member of the South Australian Council for the Ageing and a council member of the South Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

David’s leisure time was just as active. He was a member of the Rotary Club of Adelaide for 50 years and at one time its president. He enjoyed golf, fishing, boat cruising, Second World War aircraft, his houseboat on the Murray River and later his beach house at Victor Harbor. He was a committee member and captain of his golf club and a board member of the Cruising Yacht Squadron of South Australia. He was appointed a Member in the Order of Australia (AM) in 1980. In 1995 he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of the University of South Australia in recognition of his distinction in public service and service to the university.

Donald Herbert Schultz Rod Watkins

Intellectual, inventor and benefactor 1910–1987

Summary

Don was primarily interested in optometry and optics. He developed a remarkable number of optical instruments and machines, for ophthalmic and defence use. He played a fundamental role in the formation and growth of Australia’s largest group optometry practice and one of the world’s largest ophthalmic lens companies. He was a planner and participator in optometry teaching, research and professional organisation. He was an extraordinarily generous benefactor to vision research.

Background

Don Schultz was born in 1910 and grew up in the small town of Summertown in the Adelaide Hills. As a youth, he was greatly influenced by his uncle, Carl Laubman. Laubman and his friend Harold Pank had formed the optometry practice of Laubman and Pank in 1908. This was a remarkable partnership that combined a commitment to leading edge optometric practice with an emphasis on innovation and intellectual pursuit.

Don Schultz was indentured as an optical apprentice in the Laubman and Pank practice when he was a young teenager and this environment of enthusiasm, invention and intellect shaped his life. He was registered as an optometrist in 1930. He became a director of Laubman and Pank in 1944 and three years later with David L Pank, the son of Harold Pank, purchased a controlling interest in the practice.

His interest lay more in lens and instrument design than in clinical optometry or management. The Second World War forced him further in this direction.

Don established an Instrument Construction Department in the Laubman and Pank optometry practice, as a base for continuing the wartime defence work and extending into new technologies. The scope of work undertaken gives an indication of his versatility and productivity. The Instrument Construction Department carried out binocular and camera repairs. It made an optical range finder, an aerial photostereoscope, a low f-number Cassegrain telescope with a hyperbolic figure on the primary mirror, Schmidt camera corrector plates and signal lamps for the navy. In 1952, it made catadioptric cameras for the Blue Streak missile tests carried out by the Weapons Research Establishment at the Woomera Rocket Range. It made a toolmaker’s profile projector and an optical device for road marking. It made an innovative biocular catadioptric magnifier for low vision patients, a visual field screener, a Greens-type refractor head and vision screeners for industry and for children’s vision. In 1953, it became the first laboratory in Australia to use high vacuum coating technology for optical surfaces. In 1956, it patented a concept for making one-piece industrial eye protectors.

With Don’s brother, Ross A Schultz, developed lens processing machines including a lens edging machine and a diamond generator. It was during this time that Don Schultz became known for his painstaking optical design calculations that were carried out using seven-figure logarithms. There were no electronic calculators and slide rules were not sufficiently accurate. Computers capable of optical design were more than a decade into the future in Australia. Don’s book of logarithmic tables was the size of a large novel and an optical design that would today be considered relatively trivial would take thousands of lines of handwritten calculations and sometimes weeks to complete.

The move to CR-39

Laubman and Pank had been making plastic ophthalmic lenses for many years by machining them from methacrylate sheet. These lenses were light in weight but were difficult to polish accurately and were very easily scratched. Schultz envisaged casting lenses from CR-39 by creating a cavity between two polished glass moulds separated by a plastic spacer, and pouring the liquid CR-39 monomer into the cavity and polymerising it. The lenses would take the polish of the surfaces of the glass molds. He obtained a sample of the monomer but had to find a catalyst to initiate polymerisation. He approached his colleagues at the University of Adelaide, who developed a technique for making benzyl peroxide. This eventually proved unsatisfactory as the polymerised lenses were too soft and too yellow. Schultz, along with Ron Ewer, went back to the university and was helped to develop a process for making isopropyl peroxy percarbonate, the initiator that was used for the next 20 years to make several hundreds of millions of lenses. To cast CR-39 lenses in large numbers required a great deal of innovative polymer chemistry, physics, mechanical engineering and process control. The problem that confronted Schultz (and others associated with CR-39 development such as Ron Ewer) concerned volumetric shrinkage. Molecular bond formation during polymerisation caused the material volume to shrink by 14 per cent. While this was happening, it had to stay in contact with the glass molds or the lens would be defective. It was necessary to control precisely the temperature during the curing cycle, to design molds with just the correct amount of flexibility and to calculate the mold shape change during curing so this could be compensated for in the mold design and manufacture. The initial work to make a plano lens of accurate power and acceptable quality involved a large amount of experimentation and many mold designs. Don Schultz, with his seven-figure log tables and his reams of calculations, became legendary. Later when powered finished stock lenses were produced, each with a different mold configuration, these calculations had to be repeated hundreds of times.

Instruments

Perhaps the best-known of Don Schultz’s work is the development of the Schultz- Crock binocular indirect ophthalmoscope. Gerard Crock, Professor of Ophthalmology at The University of Melbourne, approached SOLA in 1965 with a prototype of the world’s first spectacle-mounted indirect ophthalmoscope. Schultz then took responsibility for designing the instrument for commercial viability. The Schultz- Crock ophthalmoscope received an Australian Design Council award for outstanding industrial design. It remained in production for the next 35 years and many thousands of units were produced and sold all over the world. Crock approached SOLA again in 1972 with an enhanced model of the ophthalmoscope, which incorporated Galilean telescopes to make retinal surgery easier. This instrument was called the COMIDO (Combined Operating Magnifier and Indirect Ophthalmoscope). In 1975, Schultz and Rod Watkins, with the Department of Ophthalmology, were jointly awarded the Prince Philip Prize for Australian Design for this instrument.

Final years

Don Shultz retired in 1976. He was awarded Honorary Life Membership of the Victorian College of Optometry in 1980. He was a Foundation Member, a Governor and a Life Member of the National Vision Research Institute. In 1987, Don Schultz was awarded the degree of Doctor of Science honoris causa by the Flinders University of South Australia for his contribution to research and scholarship in optical physics over almost 50 years. This was Don’s first tertiary qualification. Although he had taught optometry within a university for almost a quarter of a century, the optometry course he completed and taught did not provide him with either a degree or a diploma. Although he was a leading optical physicist for most of his life, he achieved this without formal qualifications and was almost solely self-taught.

Recollections of Former Employees

As I Saw SOLA 1958 – 1987 Dean Sherry

I walked through the doors of Laubman and Pank on 12 June 1958. Since leaving school at the end of 1955 I had been working at the South Australian Gas Company at its head office, 35-39 Waymouth St. Adelaide. I had a good time at SAGASCO but fortunately for me my father could see I was probably having too good a time so without my knowledge he made an appointment for me to attend an interview for a position as a trainee accountant. The Interviewers were David Pank, the Managing Director, Frank Bawden, the Company Secretary and Brian Bowler the Accountant. As it happened I got the job. No one else had applied.

The 12 June 1958 was (as they say) the first day of the rest of my life. When I started the job we had in the immediate office area the Company Secretary Frank Bawden, the Accountant Brian Bowler, a trainee accountant Roger Camp, a ledger machinist Shirley, Mr. Pank’s secretary Doreen Ryder and a records department headed by Dorothy English assisted by Helen Ingerson.

My main job was to look after accounts payable (creditors), the bank reconciliation, add up the trip reports for the optometrists who did country trips and any other mundane things that needed to be done. I also had to write invoices for one of the subsidiaries called Scientific Optical Laboratories of Australia Ltd. I can recall that most invoicing was for hi-vacuum coatings applied to glass spectacle lenses. The prices were 14/- ($1.40) wholesale and 18/6( $1.85) retail. SOLA diamond impregnated hand edging machines (manufactured by Ross Schulz) were also sold occasionally for 160 pounds ($320)

As an adjunct to this I also wrote up job cards for the Instrument Construction Department (ICD), the Camera Repair Department, the precision Optics Department (POD) and the Plastic Lens Department. All jobs had the same type of job card. Typically they were designed for one off jobs.

The most significant job card ever written was Job Card Number 6500. It simply said “Plastic Lens Project”. It was written by Ron Ewer. As I said these cards were designed for one offs so we kept adding sheets of paper recording time spent and materials used on the job. My last memory of Job card number 6500 was that together with attachments it was over an inch thick. I do not know what happened to card 6500. It probably did not survive the move to South Road.

From a work point of view everything was going ok. But I had a dilemma about the obligation to study accounting. I had left school aged 16 with the Intermediate Certificate (year 10). Study was not my long suit. Brian Bowler urged me to enrol at Muridens Business College to do Intermediate book keeping during the last half of 1958. I enrolled but did not pass the exam. Not good start. In 1959 I enrolled at the South Australian Institute of Technology to do a book keeping course that was a pre-requisite to starting the accounting diploma. I attended every lecture and every tutorial. Bit by bit the penny began to drop. I was getting the idea of what book keeping was supposed to do.

I passed the exams and started the accountancy course in1960. This was an important year as SOLA started in its own right on 1st July 1960.

The normal way to start accounting studies on a part time basis is do Accounting 1 and Auditing 1 in the first year. I was encouraged to do an additional subject to accelerate my progress through the course. I enrolled in Mercantile Law 1. For me it would have been easier to read and write Japanese than to understand what Mercantile Law was all about. I failed but did pass the accounting and auditing subjects. The failure in Mercantile Law prompted the first fire-side chat with Mr. Pank. During this friendly little session I was told in no uncertain terms that I would be out the door unless I lifted my game. “We are not interested in clerks, clerks are a dime a dozen, I can go out into Gawler Place and get a dozen clerks, What we want is an accountant.” David really had the capability to chew you up and spit out the little pieces. But this session worked for me. There was no way I would allow myself to be subjected to such an onslaught, not ever.

So that meant I just had to do Mercantile Law. I enrolled in 1961 for Accounting 2, Auditing 2 and Mercantile Law 1. As it happened, Noel Roscrow also enrolled as part of a management course he was doing. Noel had the same experience I had had the previous year and he soon departed. I still have both his and my text books in my home.

Again the penny started to drop and I finally got a hold on Mercantile Law and passed all exams. I now had 5 of the 11 subjects required for the diploma. It was vital to get knowledge of Mercantile Law as there were more law subjects than accounting subjects in the diploma. Thereafter I did not drop another subject and in fact I was getting better as the subjects became more complex. Credits and distinctions started to appear. I was thrilled to my back teethe when in my final year I achieved the second highest distinction for Income Tax Law and Practice and 4th for Bankruptcy Law and Practice. The final footnote is that on the day of receiving my final results I was having a drink( was I ever) at the Oriental Hotel (corner Rundle St. and Gawler Place - now well gone) and David Pank walked in, congratulated me and gave me a bottle of champagne (well you know a Seppelts sparkling ). I have never forgotten that.

SOLA at Gawler Place

SOLA commenced business on 1st July 1960.

Prior to this, Scientific Optical Laboratories had been used as a tax minimizing vehicle.

In those days the income tax law allowed. In those days private companies received a tax break of 10% on the first 10,000 pounds ($20,000) of taxable income. If the standard company tax rate was say 35% then on the first 10,000 pounds the tax rate was 25%.

Further, groups of companies were taxed as individual entities. Therefore, it made sense to have one or more subsidiary companies splitting the income of the business.

Also, at that time payroll tax was levied by the Commonwealth Government. Payroll tax was a straight levy of around 5% of gross payroll. However, there was a tax free threshold. If your total payroll was below the threshold then no payroll tax was payable.

So SOLA purchased spectacle frames and lenses and then simply on sold them to Laubman and Pank. This diverted taxable income from Laubman and Pank to SOLA. This was not sophisticated tax minimization but it was effective and quite legal.

As I said earlier SOLA was also engaged in hi-vacuum coating of glass spectacle lenses. The colours were Solatan and Solagrey.

So SOLA gets under way on 1st July 1960. Sales of Rx plastic lenses amounted to 7 pounds ($14) for the month.

Whilst I continued to do my Laubman and Pank jobs the SOLA work was steadily increasing. I also began to work with Noel Roscrow on Laubman and Pank’s Edging and Surfacing Departments. But the best issue for me was that I was able to write up the General Ledger (in those days called the Private Ledger). In fact I was doing all of the accounting for SOLA. Whilst there was really not all that much in the earlier days it did give me the opportunity to gain experience and as it happened SOLA and Dean Sherry grew together. It was also the most junior task in the Laubman and Pank Accounting Department. Brian Bowler and Roger Camp were involved in the more complex accounting functions of Laubman and Pank.

SOLA at Black Forest

I remained at Laubman and Pank until 30 June 1963 but my involvement in SOLA was increasing day by day and I was spending more and more time at the new premises -371 South Road, Black Forest SA. (This building still stands and is now number 649 South Road.)